KURDISH TATTOOING

Henry Field expanded on Smeaton’s studies of Iraqi Arab tattoo to include other ethnic groups that inhabited the region, like the Kurds of northern Iraq, as well as indigenous populations living in southwestern Asia. Of considerable interest are his ethnographic notes focused upon the Kurds who live today north of Baghdad and in parts of Syria, the Caucasus, and Iran.

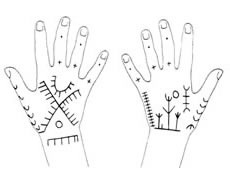

Kurdish women’s tattoo designs from Iraq, ca. 1930.

The history of the Kurdish people is as complex as it is ancient. By the middle of the 2nd millennium B.C., the culture and society of Kurdistan appear to have been unified under the Hurrians, a people who spoke a language belonging to the Caucasian family distantly related to modern Georgian and Laz. The fundamental legacy of the ancient Hurrians to the contemporary culture of the Kurds is manifest elementally in their religion, mythology, martial arts, genetics, and tattoos. But other religions left their mark on the tattoo traditions of the Yezidi Kurds, including the Aryans who extinguished the last Hurrian states in the Zagros-Taurus mountain regions by 850 B.C.

Today, the Yezidi Kurds comprise less than five percent of the entire Kurdish population, but their tattooing traditions remain, as do many of their religious ceremonies like the Jam. Held at the sacred shrine in modern Lalish, Iraq, Jam coincides with the great Aryan festival of Mithrakan which celebrated the act of world creation by the sun god Mithras. The earliest known reference to Mithras dates to the 14th century B.C. and according to clay tablets excavated on the Anatolian plateau, he was worshipped for over two-thousand years. The Roman Emperor Commodus (180-192 A.D.) even brought “the cult of light” to his empire and afterwards Roman emperors more and more identified themselves with the Unconquered Sun, took the title of “Invictus” and wore a crown with sun rays.

According to Izady, Kurdish men and women still wear tattoos (kutra’i in Kurdish) associated with Mithras. Some of the motifs are found adorning the outer walls of the Yezidi shrine at Lalish:

The symbol combining a dog, a serpent hole, and the sun disc used by Yezidi women is a fascinating reminder of this combination in ancient Mithraic religious sculptures (the sun god Mithras killing the bull of heaven, from whose blood springs a serpent and a dog, the symbols of balancing forces of good and evil).

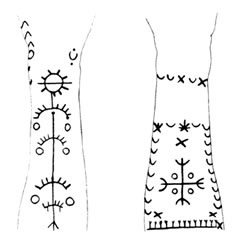

Yezidi men’s hand tattoos from Iraq, ca.1930.

Field remarked that the Yezidis tattooed most frequently a comb design, called misht or meshed, and a rayed circle or disc with a varying number of rays and sometimes a circular branded scar called kawi in the center. Westermark illustrates a related tattoo motif in Morocco which was called mechta, “comb,” very similar to the etymology of the Kurdish word misht, that resembles the carding comb tattoos of the Kabyle and Chaouian Berbers of Algeria. Cola Alberich reported that rayed crosses tattooed in Morocco were “expressions of the solar cult.” Thus, it seems that comb tattoos in Iraq were perhaps in some way related to solar motifs, because we know that iron carding combs and tattoos were used as fire symbols in North Africa.

As such, we see in the dominant motifs of Kurdish tattooing the value of a type of “holy formula” that Izady says “cannot be altered without losing its power. These markings are of considerable antiquity, and are ‘living’ examples of many ancient motifs preserved in this way.” In this vein, rayed semicircles enclosing a star and two dots were said by some Yezidi women to ward off the evil eye, while other tattoos were therapeutic used to cure rheumatism and headaches because of their perceived healing properties. It should be noted that tribal peoples in Iran also practiced these forms of medicinal tattooing.

Yet other authorities have argued that because the sun brought forth the new growth of plants, coinciding in a sense with animals giving birth to their young each spring, the heliolatrous significance of the tattooed cross, as a solar symbol, connoted procreation and ultimately served as a fertility mark; whereas the swastika, present in tattoo traditions of the Kurds, Berbers and indigenous groups in India, metamorphosed into a related form (via spirals, concentric circles, and rosettes). However, the sun ideograph may have also represented deified fire symbolizing properties of purification.

Source: Tattooing in North Africa, The Middle East and Balkans

By Lars Krutak

Thanks for sharing, great info, a lot of these symbols are cross-culture as well, some of them are exactly like Slavic and Balkan ancient symbols : )