Datsueba

Japanese, Edo period, 1845 Kikuchi Yôsai, Japanese, 1788–1878 (Boston Museum of Fine Arts)

I was reading a fascinating account about the possible origin of Baba yagas by Sergei V. Rjabchikov from his “The Scythian and Sarmatian Sources of the Russian Mythology and Fairy-Tales” when I began to think of all the similarities between the Russian “crone” and the Japanese mountain crone or hell’s hag (Shozuka- /Sanzu- /Jikoku-no baba). As I began to investigate further the Russian baba yaga, I discovered that many East European or Slavic countries and Central Asian peoples also possess uncannily similar folkloric versions of stories of the old hag or crone. That there should be such larger-than-life folkloric character-sharing with so many similar features existing across so many cultures, says to me that the universal old crone legend must have had great significance to have survived over at least thousand years, and to have been passed on through the generations and across so many empires’ borders. It also indicates a large swathe or huge spheres of cultural interaction where the Baba yaga/Hell’s Hag stories could have been passed on in a “Chinese whispers” sort of way, as a result of either cultural or demic diffusion…yet without losing much of the essence or spirit of the Baba yaga character. To begin with, we go through Rjabchikov’s version, excerpted below and key elements bolded:

From an ancient crypt in Crimea, Ukraine comes images of…

“…a fiery horse, a hut standing on four chicken legs (as in Russian fairy tales!) and a woman (goddess) with the fiery hair. A child is seen in this fairytale hut. These data correspond to the Russian fairy-tales about Baba-Yaga (the old woman Yaga).

I think that the personage Baba-Yaga corresponds to the Scythian goddess Tabiti. I have counted ten rays at her head in this figure. The face of a goddess is represented on a Scythian brooch discovered in the Belyaus burial ground, the Crimea, Ukraine (Dashevskaya 1991: 121, table 65, figure 10). It is a designation of Tabiti whose head is decorated with nine or ten rays. As has been shown earlier (Rjabchikov 2001a), Baba-Yaga (cf. Old Indian yaga ‘sacrifice’) is closely related to the fire god Agni. Actually, this god plays the main role in sacrifices according to the Indo-Arian mythology (Neveleva 1975: 85).

Let us examine some features of Baba-Yaga. V.Y. Propp (1998: 147) stresses her roles of a donor, an abductor, a female warrior. The last function is in my opinion a hint at the Amazons, otherwise the Sarmatian women. In Baba-Yaga’s hut the initiations are performed (Propp 1998: 157). She denotes the fertility without the participation of men (Propp 1998: 168); she directs winds; she keeps keys from the sun (Propp 1998: 169). As an ancestress she is connected with the hearth (Propp 1998: 171). She gives her horse (Kobylitsa-Zolotitsa ‘The Golden Mare’) to a hero (Propp 1998: 172). Some epithets of the horse which is equal to the god Agni are “with a golden mane”, “having a light-coloured back”, “with a fiery head” in the Indo-Arian beliefs (Propp 1998: 264). The main attributes of Baba-Yaga are the fire and the horse (Propp 1998: 190, 197). Besides, she is preparing a youth for a marriage; she is burning or boiling children (Propp 1998: 198, 200).

Baba-Yaga’s hut stand on chicken legs? First of all, Old Indian kukkuta means ‘cock; hen; fire-brand; spark of fire‘. So such legs may correlate with the cult of the fire…

Baba-Yaga knows the future and betokens (Afanasiev 1996: 57). And now one can examine an information about the Scythian goddess Tabiti mentioned in the History of Herodotus (Book IV): she compares with Hestia, the Greek goddess of hearth and home who is a virgin and the eldest sister of the god Zeus (1). All these features fit the features of Baba-Yaga (hearth; initiations; without a husband; connected with winds). The edges of roofs in the ancient town Panticapeum, the capital of the Bosporan kingdom (modern Kerch, the Crimea, Ukraine), were decorated with masks of a goddess (Blavatsky 1953: 173, figure 7). Since her hair is shaped like tongues of flame or rays of the sun, this is Tabiti, the goddess of hearth and home. It is well to bear in mind that D.S. Raevsky (1994: 204-5) points to the similarity of Tabiti (Tapayati ‘Heating; Flaming’) to Agni. In a Scythian inscription I read the words Tabera vese ‘Knowing Tabiti’ (Rjabchikov 2001a). The names Tab-iti and Tab-era (cf. the Russian suffix ar) ‘Heating; Flaming’ are the variants. One can suppose that the Scythians translated the name Tabiti as Ta biti ‘Beating’ (Trubachev 1981: 23), too. The beating Baba-Yaga is also known (Propp 1998: 180-1).

The goddess Tabiti is depicted on a gold badge discovered in the Chertomlyk barrow, Ukraine; it was dated to 4th c. B.C.”

— End of excerpt…

One wonders how much of a connection Baba-Yaga has with the Japanese myths and folktales of the Sanzu no Baba 三途の婆= Shōzuka no Baba=Jigoku no Baba 地獄の婆=Datsueba who are varying folk versions of a hideous creature or “hell’s hag”. Shozuka-no-Baba or Datsueba who strips children of their clothes on the Sanzu river banks of the Buddhist Underworld (or in other folkloric versions – Sainokawara, the Japanese River Styx), and then encourages them to make piles of stones to build a stairway to paradise. The afflicted children are then consoled and saved by the very popular Jizo Bodhisattva, (alternatively, Ksitigarbha) who hides them in the wide sleeves of his robe.

In the Japanese context, the Jikoku no Baba lit. “Hell’s Hag” or Datsueba, “Old Hag of Hell” is obviously related to death or funerary customary practices because it occurs in the context of the Sainokawara which is the Riverbed of Souls in Purgatory or sometimes interpreted as the Limbo for Children) with Jizo guiding dead souls safely in the crossing of the River Sanzu (Sanzu No Kawa 三途の川, River of Three Roads, River of Three Crossings. River Sanzu would ring a bell for most, with echoes of River Styx and an Orpheus-like Underworld.

Overall, there are enough common elements between the Japanese hag and the Slavic/Uralic Permyak/Sami/Mansi)/Scythian/Siberian ones to suggest a (lost or forgotten?) funerary Underworld context as well to make us ponder the possibility of a universal “Baba yaga” and the probable route of diffusion to the “Baba yaga” countries:

- Baba-yaga is a hag, crone or witchlike person or seer/fortune-teller (Romani gypsies) In Tibet, the Yagas are thought to be either Bon Po demon-and-fire-worshippers or the fierce demons themselves: Grandmother Demon, Grandmother Dragon. The Hungarian bábák meant “old woman”, originally a good fairy with magical abilities who in later eras was regarded as having become degraded and became evil. She was thought to live in fountains, and if young children went too close to her lair, she lured them in. She was also thought in mythology to have possessed a táltos shamanic function and able to fly between the Upper/Middle/Underworlds on the back of a horse, so one of the theories about the ancient Hungarian religion is that it was a form of Tengriism, a shamanistic religion common among the early Turkic, Uralic and Mongol people, that was influenced by Zoroastrianism when the Magyars (perhaps the Arpad-Attila the Hun lineage) encountered the Persians during their westward migration.

- Baba yaga tortures or kidnaps small children, sometimes grilling or boiling them! (although the Greek Persephone as daughter of Demeter (Mother Earth) is the one being abducted by Hades to become his Queen of the Underworld). Alternatively, Baba yaga is sometimes the force behind urging children to behave …as well as delivering what goes around comes around to unsavory stepmothers.

- Baba yaga is often described as tending the fire / water /or gathering herbs or rearing the animals … in such a role, she is akin to an underworld goddess who rules over the forces of life, death and fertility. See Grandmother Gaia: Baba Yaga stories) Sumerian BAÚ was believed to be the goddess of bounty, a healer, and a provider of harvest and food, giver of birth and fertility and often called Mother BABA, and the life giver (midwife) who helps bring life into the world, while her Hungarian counterpart was Boldog Asszony, goddess of birth, fertility and harvests. Dumuzi, god of the Underworld was a vegetation god as well as a harvest god of ancient Mesopotamia, — he was the son-husband of the goddess Gula-BAU. [Note: Hungarian-Sumerian-Russian fertility-birth-Earth’s womb-Underworld-mother goddesses … all are called Baba, along with the Ob people’s Zlata Baba, the Golden Woman or more properly, the Lumiinous and Radiant Dame, but there is also the Khanty’s goddess Kaltash-ekva, the deity the birth-giving goddess who dispatches the souls of the children to be born, also the goddess of dawn, wife of the sky god and who keeps account of the length of people’s lives. Japanese Demon Lore suggests that the Jigoku no baba / datsueba and yama-uba (Mountain Hag) reveal the dichotonous nature of the goddess of birth and death. The earliest attested form of Demeter’s name in Mycenean Greek is Da-ma-te, Da meaning “earth” and the second element of her name meter (μήτηρ) derived from Proto-Indo-European *méh₂tēr (mother). So Demeter is “Mother-Earth”.

- In some legends Baba Yaga is also awarded the title Костяная Нога (“The Bone Leg”) and considered a guardian between the real world and the land of the dead. She is known on rare occasions to offer guidance to lost souls. Hecate, the Greek triple goddess plays such a role and becomes attendant to Persephone and guide of in the Underworld. Hecate is thought to have originated in the Hekat of the Carians of Anatolia, where ((like the Japanese Jizo) she has a succouring role of savior and variants of her name are found to be names given to children, although classical Athens traditions associate her with witchcraft and refer to her in the Goddess’s aspect of the “Crone”.

- A chicken motif (suggesting the ancient votive offering/cock symbolism in funerals) – the cock is seen on a boat heading towards the sun (solar deity) in many Underworld myths or iconographies. Ceramic cockerel or chicken haniwa are the most numerous type of bird tumuli terracotta artefact, followed by waterfowl, found during the Tumuli Kofun Period in Japan. The Persian Avestan (Indo-Iranian) Sraosa, attendant to the Sun god, guides the souls of the deceased to find their way to the afterlife. His symbolic animal is the cock, whose crowing calls the pious to their religious duties. (Sraosa, killer of demons, is opposed by archdemon Aesma Daeva together with other Underworld female demons). A hen and cock (along with two horses) were sacrificed as part of the Norse funeral rituals, presided over by an old woman referred to as the “Angel of Death” who was responsible for the mortuary rituals. Cock symbolism and terracotta were also used by the Romans. The Russian/Slavic interpretation of cock and hen usage however, is that it relates to the use of magic and for al healing spells (p. 166).

- Baba yaga’s hut is surrounded by a palisade with a skull on each pole, or both. The fence with a skull on pole (overtly a mortuary and/or sacrificial ritual function) or the fence outside is made with human bones with skulls on top, often with one pole lacking its skull, leaving space for the hero or heroes.

- The hut (funerary context -perhaps interim holding hut see Khanty burial house) connected with horse (Scythian and Siberian afterlife horse (and chariot) riding towards the sun cosmogony motif) In “some tales, the hut is connected with three riders: one in white, riding a white horse with a white harness, who is Day; a red rider, who is the Sun; and one in black, who is Night” (see Baba-yaga). Baba Yaga, hints of the old horse-Goddess cults predating classical Greek culture (see Hag of a Muse)

- The element of animal or human sacrifice – horses, cocks, and also cows or sheep or human sacrifices were made but the horse was symbolic of a mount for the deceased and the cock, a solar guide through the Underworld towards Dawn/sun (a remote memory perhaps alluded to by the burning and grilling of bones. Ritual child sacrifice and urn burial, the most famous examples of which are those held at Tophet, by Canaanites and Carthaginians and the practices of the ancient Near East. The Tibetans’ pre-Buddhist mortuary rituals included a sacrificial requirement of a holy triad of horse-sheep-yak — the sheep as guide to make their way across clips and rivers; and the yak to confound or combat the demons. Sometimes, a human “ransome” sacrifice was donee.

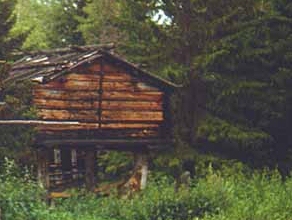

- In the Russian tales, Baba yaga lives in a log cabin that either stands on or moves around on a pair of dancing chicken legs. The Sami have a storehouse that looks exactly like it with the “chicken feet” (see photo below). In Slavic traditions, there is also a death hut (see sketch below).

- Siberians, Ob-Ugrians hold figurines of their gods in such huts or doll-like effigies in rags in a small cabin on top of a tree stump that fits a common description of “Baba Yaga, who barely fits her cabin: her legs lie in one corner, her head in another one, and her nose is grown into the ceiling”. However, the doll is said to be a repository for fourth and renascent, reincarnating soul of the deceased(see Edgar Saar) and is not representative of a deity nor of Baba Yaga as such. The Golden or Radiant Lady of the Dawn called Zolota Baba or Slata Baba, is whom the Ob-Ugrians (Khant-Mansi) revere the most, and pray to and consult for all things. The title Golden or Radiant Lady of the Dawn recalls the solar nature (cock calling at dawn or guiding the boat of the dead towards the sun), a character that has strong parallels with Amaterasu sun goddess of Japan emerging out of the Cave.

Left: Sketch by Nicholas Roerich, Izba smerti of the Hut of Death, 1905, an artistic expression of burial traditions of the ancient Slavs

Right: Sami storehouse, Stockholm, Sweden

Above: Shogoso of the Shosoin, Nara

Below: Storehouse of the Khanty-Mansi (Ob-Ugrians)

The Russian and East Slavic folkloric Baba yagas seem to be characters who have become detached or removed from the original funerary-Underworld contexts, though that mortuary context is still secure in the Finno-Ugric/Norse/Japanese contexts (except for the Japanese Yama-uba mountain crone variant). The Baba yaga in the Russian/Slavic cultures have become “forest demons” or “forest spirits”, writes Andreas Johns in “Baba Yaga: The Ambiguous Mother and Witch of the Russian Folktale“(p. 162). But even in the East European context, Baba yaga’s funerary role re-surfaces again as Sergei Rjachikov in his article uncovered the Baba yaga figure in the ancient Ukrainian crypt, although Rjachikov’s purpose and focus was to try to establish an Indo-European origin for Baba yaga.

While the Japanese figure of Shozuka-/Sanzu-/Jigoku- no-Baba appears closest perhaps to the Khanty-Mansi Radiant Dawn-Zolota Baba figure especially because of the riverbank and cairns setting.

Other Japanese tomb iconography of the Yayoi and Kofun tombs show boats with a cock at the helm journeying towards the sun….pointing to either Persian influence point to either Persian or Vedic Indian influence via the imagery of Sraosa as a guide in the Underworld with cock towards the Sun Ahura Mazda or the Indo-European equivalent seen in India’s Indra, a.k.a. Sakra (lord of heaven, war and thunderstorms), who pushes up the sky and by smashing of the Vala stone cave or alternatively cow enclosure, he releases Ushas, the most exalted Dawn goddess (parallels in Zolota Baba and especially in the Amaterasu myth). Twenty of the 1028 hymns of Rig Veda are dedicated to Ushas whose role of warding off evil spirits of the night, and as a beautifully adorned young woman rides in a golden chariot on her path across the sky. Indra is also described as golden-bodied and having a function as one of the guardians of the directions – of East, and deceased warriors go to his hall after death, where they live without sadness, pain or fear. There is also a Near Eastern connection since the name of Indra (Indara) is also mentioned among the gods of the Mitanni, a Hurrian speaking people who ruled northern Syria from ca.1500BC-1300BC (source: Indra).

The solar aspect of cock symbolism is however, is given fullest treatment in the Legend of Archer Yi shared by East Asians – the Miao, Yi and Korean peoples:

“The sun rises and sets at fixed times; you do not yet know the laws of day and night; it is absolutely necessary for you to take with you the bird with the golden plumage, which will sing to advise you of the exact times of the rising, culmination, and setting of the sun.” “Where is this bird to be found?” asked Shên I. “It is a three-footed bird, which perches on the Fu-sang_ tree [a tree said to grow at the place where the sun rises] in the middle of the Eastern Sea. This tree is several thousands of feet in height and of gigantic girth. The bird of golden plumage had a sonorous voice and majestic bearing. It lays eggs which hatch out nestlings with red combs, who answer him every morning when he starts crowing. He is usually called the cock of heaven, and the cocks down here which crow morning and evening are descendants of the celestial cock. This bird keeps near the source of the dawn, and when it sees the sun taking his morning bath gives vent to a cry that shakes the heavens and wakes up all humanity. Go and fetch it and take it to the Palace of the Sun” [think of Indra’s Hall]

Fred Hamori in “The goddess of birth and fertility” relying on the work of Dr Ida Bobula, “A Magyar ösvallás istenasszonya” goes to great lengths to establish the very ancient Mother Goddess BAU, the Sumerian/Mesopotamian goddess of birth and fertility as the pre-cursor or proto-type for the Hungarian, Bulgar, Finno-Ugric, Turkic and Mongol-Hun mother- harvest-cum-Womb-of-the-World type goddesses.

So far, the solar goddess, the fertility goddess and regenerative earth goddess have been hinted at. But the Russian Baba yaga and Japanese Jigoku baba are darker creatures … crones, hags or “demon”-like creatures, like the Iranian, Indian and Tibetan images, which suggests to me there was a transformation of the Old Woman images– they became more and more demon-daeva-like moving Eastwards across Eurasia. The witch-like images may have been a transformation following Christianity’s move to stamp out paganism.

The concept of the Old Woman Stone or Ubaishi comes to mind here. In “Immortal wishes: labor and transcendence on a Japanese sacred mountain, Ellen Schattschneider writes of that the “important destination of shugyo (ascetic discipline) on Akkaura mountain is the sacred rock of Ubaishi (Old Woman Stone) high on the left ridge above Akakura gorge. Ascetics are expected to crawl through a tunnel under the boulder six times, a process that recalls birth as well as passage throught he six realms of creation (rokudo) and which has associations with an important episode in the Kojiki .., in which the sun goddess Amaterasu emerges from a cave”. Amaterasu could be interpreted as “Ama”=”Mother” although current interpretations have it as meaning `Sky’ or `Heaven’ and “terasu” according to consensus views means “to shine” or “shining”, but “terasu” actually sounds like an close phonetic sounding out of “Th-ra-ce”, so my conjecture would be that Ama-terasu could actually mean “Mother of Thrace”. In other words, a ‘Mountain Mother’ that came out of Thrace’s sacred mountains and caves.

In Mountain goddesses in Ancient Thrace: The Broader Context Nikola Theodossiev argues a good case for an origin of the `Mountain Mother’ in Thrace’s mountain cult sanctuaries for many of the Greek and Phrygian (Asia Minor) gods, “Mountain Mothers” including Cybele, Zerynthia (aka Hecate/Rhea), Tereia, Gaia, Rheskynthion, Dindyma, Ganea/Ganos and the male gods too: Saon/Saoke/Saos, Apollo, Orpheus, Zalmoxis (a.k.a Zeus).

According to Theodossiev, this borrowing of Thracian ‘Mountain Mothers’ was widespread in Greece and Asia Minor, and the process by which how this could have happened is explained thus:

In the context of all these written sources is the great number of Thracian sanctuaries located in mountains and rocky highlands that clearly show the sacred nature of the places. Also, it is possible that the numerous tumuli of ancient Thrace might symbolize sacred mountains and if so how these burial constructions could be related to some cults of mountain goddesses besides their funerary functions. … A similar syncretic process could be traced back in the literary works of the late 5th century BC … In fact the literary image of Rhea as `Mountain Mother’ was probably created in the interaction zones of Asia Minor, where the idea had been borrowed from the non-Greek people. The literary image of the ‘Mountain Mother’ survived well into the Roman Imperial Period.

On late Hellenistic silver bowl [supposed to have come from Asia Minor or Thrace] … a brief inscription is incised … in translation “Koteus [son/servant of `Mountain Mother’ … In both cases this inscription is remarkable evidence for religious ideas and cults related to the mountain appearance of the goddess.

Although Thrace is a long way away from Japan, Thracian ideas obviously had great impact in the Hellenistic and Asia Minor scheme of things, and its influence was undoubtedly also spreading eastwards throughout the Greek-Bactrian-Margiana-Ferghana sphere of interaction into Southwest China and Northern China via trade or nomadic expansions along the Silk Road terminating at the Japanese archipelago. We could conceive this was how not only the Baba yaga or the Mountain Crone character, but also the mother and mountain goddess-Sacred Cave concept came to be so widely implanted across Eurasia.

In 1928 Professor Popp wrote a brilliant book on connection between Russian fairy tales and initiation rituals. He offered many insights which I have no time to list but you might be interested in. See

http://www.lib.ru/CULTURE/PROPP/skazki.txt

Is there an English translation do you know?

By the way, he (and many other Russian scholars) indicated that the image of “chicken legs” might be due to a mistranslation. The original phrase might have referred to stumps under a funeral hut.

Possibly the scholars are correct (if so, certain depictions and illustrations of the huts would also be false?) but in any case, the funerary connection is established, the cult rituals of hanging dead animal sacrifices and chickens on the fences or poles, of impaling skull bones, suggest the distinct connection and make it likely that imagery existed somewhere in the past. At the Ise shrine, the cocks roam everywhere around the shrines that are a grander version of these huts. The architecture of the funerary log-huts (or which may have doubled up symbolic functions as granary/weapon storehouses in some cases) also appears to have been prevalent among a number of cultures cross the Caucasus, Altai, to Japan.

[…] Here’s a more in depth look at some similarities between Slavic and Japanese folkloric old ‘hags’. […]

[…] [1] Népmeséink kacsalábon (csirkelábon) forgó kastélya valójában az uráli népek halottasháza. Levágott fák törzsére épült kunyhóféle, melyben az elhunyt lelke közelebb van az éghez (az égig érő fa tetejéhez) így könnyebben feljut a lelkek birodalmába. A népmeséinkben, (s az uráli, tatár, mongol és szláv népmesékben is), szereplő kacsalábon-csirkelábon forgó kastély a halál allegóriája. A hős a táltos, aki valójában a halálból menti meg a lányt. https://japanesemythology.wordpress.com/comparing-japanese-mountain-crones-or-hags-yamaumba-jigoku-n… […]

[…] Here’s a more in depth look at some similarities between Slavic and Japanese folkloric old ‘hags’. […]