Ho-ho bird

In this article, we aim to look at the various forms of the Phoenix in Japan, and compare its iconography with that found elsewhere.

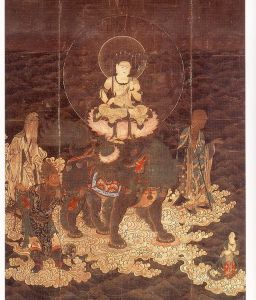

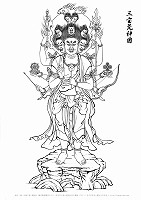

In Japan, the phoenix is identified as the Ho-ho (alternatively, ho-o) bird. As is common in east Asia, it is a sunbird … the sun is often represented in the art form of a bird. The ho-ho bird is a messenger of goodwill comes to earth and sits on top of the torii. Below are some of the early representations of the phoenix in Japan and its neighbours in East Asia.

A very early art representation of the phoenix in Japan is the Vermilion Bird (Suzaku) in the 7th -8th c. Kitora Kofun tomb in Asuka, Nara, for more details, visit Steve Renshaw’s “Kitora Kofun” astronomy homepages.

Suzaku, Red Bird of the South, (Image credit: National Research Institute for Cultural Properties, Nara)

Similar iconography may be found in the Red phoenix (one of the Four Guardian Deities, defenders of the four directions on each wall to guard the soul of the deceased against demons), Kangso Middle Tomb built between the second half of sixth century and the first half seventh century AD, Namp’o, North Korea Image credits: Yonson Ahn, Japan Focus

Both the Korean and Japanese Four Guardian Deities tomb murals are evidence of the reach of the Chinese Han dynasty empire. See a comparable Han dynasty example of the Red Bird below:

The Vermilion Bird on the gates of a Han Dynasty Shen family mausoleum complex in Sichuan, China Image: Wikimedia Commons

The Simurgh in Uzbekistan (see tile mural below) is a more graceful birdlike form resembling the Chinese and other East Asian phoenixes, while the Saena depicted with peacock-tail on Sassanian silk (next next image below) takes on more composite bestiary fantasy forms. A diversity of art iconography and storylines are found in Persia.

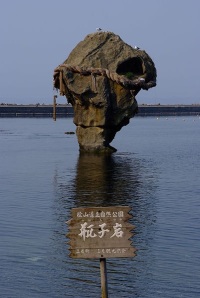

Simurgh or Phoenix decorative motif outside of Nadir Divan-Beghi madrasah, Bukhara, Uzbekistan

In one late version of the Saena bird, the bird is said to have carried Rustam the Persian cultural hero off to China.

Simurgh motif on a piece of Sassanid silk textile of the 6th – 7th c. Image: Wikipedia

***

The Simurgh (/ˌsɪˈmərɡ/; Persian: سیمرغ), also spelled simorgh, simurg, simoorg or simourv, also known as Angha (Persian: عنقا), and Anka (Arabian) is a benevolent, mythical flying creature. The figure can be found in all periods of Greater Iranian art and literature and is also evident in the iconography of medieval Armenia, the Byzantine empire, and other regions that were within the sphere of Persian cultural influence.

While the task of sorting through the variant evolving versions of the phoenix symbol (both art iconography and mythical tradition) is fraught with difficulty, tracking down the source(s) of the iconic Phoenix can theoretically be done by tracing a number of characteristics back through time and across geographical locations and space, linguistic etymological variants and the mythical descriptions as well as iconic artwork. We will make an attempt at a series of observations about the origins and evolutionary phases of the iconic Phoenix symbol.

First, a number of preliminary observations about the early phase in the evolution of the phoenix:

a) The Indo-Iranians seem to have started out with a tale of two birds — two raptor birds – falcon or eagle-hawk types: the Syenah/Saena and Cīnāmrōš/(C)amros/ (C)amru.

b) On etymological cognates and groupings based on linguistics: Avestan mərəγō Saēnō and / Saena (also Turkic)/ Sanskrit śyenaḥ (read a version of the tale here)

The Middle Persian term derives in turn from Avestan mərəγō Saēnō “the bird Saēna”, originally a raptor, likely an eagle, falcon, or sparrowhawk, as can be deduced from the etymological cognate Sanskrit śyenaḥ (“raptor, eagle, bird of prey”) that also appears as a divine figure. Saēna is also a personal name, which is root of the name.

c) The Saeno-Saena-Syenah-Xarnah group of bird icons have to do with fortune, health and wealth or prosperity, including nourishing rain for a bounty of crops. Saena is a rain-bringer (with a role much like a sky- or thunder-deity’s)…this characterization datable to 6th century BC through 2nd century, CE.

In the Avestan Yašt 14.41 Vərəθraγna, the deity of victory, wraps xᵛarnah, fortune, round the house of the worshipper, for wealth in cattle, like the great bird Saēna, and as the watery clouds cover the great mountains, which means that Saēna will bring rain. In Yašt 12.17 Saēna’s tree stands in the middle of the sea Vourukaša, it has good and potent medicine, is called all-healing, and the seeds of all plants are deposited on it. This scanty information is supplemented by the Pahlavi texts.

The bird Cīnāmrōš (Camrōš) collects the seeds and disperses them where Tištar (Sirius) will seize the water with the seeds and rain them down on the earth. While here the bird breaks the branches with his weight, in Bundahišn 16.4 (tr. Anklesaria) he makes the tree wither, which seems to connect him with the scorching sun. An abbreviated form of this description is found in Zādspram 3.39; a gloss on the Pahlavi translation of Yašt 14.41 confuses the tree of many seeds with the tree of the White Hōm. Two birds are involved in the scattering of the seeds also in the New Persian Rivāyat of Dārāb Hormazyār (tr. Dhabhar, p. 99), here called Amrōš and Camrōš, Amrōš taking the place of Sēnmurw; these names derive from Avestan Amru and Camru, personal names taken from bird names.

d) Simurgh is said to be derived from Middle Persian Pahlavi Sēnmurw (and the earlier Sēnmuruγ), also attested in Middle Persian Pāzand as sīna-mrū.

Cinamros-and Sina-mru transform easily into the Central Asian Turkic cognate Samrug falcon- or eagle-like raptor.

–>In Central Asia, Samran, and Samruk.

—> In Persia, Sēnmuruγ–> Senmurw—>Simurgh

—–> in West Asia, Semrug, Semurg

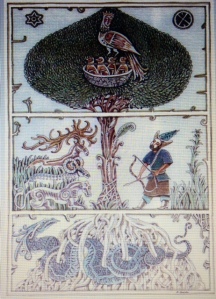

In Kazakhstan, the official version of the Samruk legend goes as follows:

“In the centre of the composition is a depiction of the Baiterek Tower, a monumental structure representing the ‘tree of life’ with a large ‘egg’ nestling in its branches. The monument is situated in the centre of Astana and it has come to represent the thrusting ambitions of the capital and the country itself….

At the base of the Baiterek motif, there is a decoration symbolizing ‘birds wings’ which refers to the mythical sacred bird Samruk, which is associated with freedom and happiness (in Kazakh mythology, the Samruk lays its golden egg in the Baiterek or poplar tree and when the Samruk flies away, a snake eats the egg… The bird returns a year later, lays another, and the snake eats it and so on… ). Like the legend of the phoenix, the tale of the Samruk is a regeneration myth that suits Kazakhstan well.” — Embassy of Kazakhstan

Local folklore adds a few more details, ”

“> Kazakh legends have it that on the World River bank, there grows the Tree of Life, called Bayterek. Samruk the holy bird of happiness is flying to it to lay a golden egg in the nest, located on its top. The egg symbolizes the Sun, granting life and hope. But beneath, there is Aydakhar, a wicked dragon, hiding among the roots, and wishing to eat the egg.” –photo of Baiterek credit: Advantours

Kazakh legends have it that on the World River bank, there grows the Tree of Life, called Bayterek. Samruk the holy bird of happiness is flying to it to lay a golden egg in the nest, located on its top. The egg symbolizes the Sun, granting life and hope. But beneath, there is Aydakhar, a wicked dragon, hiding among the roots, and wishing to eat the egg.” –photo of Baiterek credit: Advantours

The Persian-Iranian Simurgh evolved diverse forms … according to Magickal, Mystical Creatures: Invite Their Powers Into Your Life by D.J. Conway:

The Early Persian Sinamru was an immortal half bird-half mammal or dog-bird, with access to two worlds –>

The Sasanians’ Senmurv was a dragon-peacock with role of friend and helper, healer and an enemy of snakes –>

The Simurgh’s giant bird beast that’s part lion-peacock-snake-griffin, lived where haoma grew—>

Simurg is a benevolent giant bird that nested in the highest peaks of Alburz mountains Of North Iran … He helped a wizard bring Rustam into this world with the help of magical feathers, Rustam is a giant —>

11thc. Simurg and Rustam defeated evil prince Isfandiyar with magical feathers —>

The Iranian’s Simurgh is a noble vulture, that helps the adventurer on his journey who is trapped in the Underworld to get back to the middle world.

The Metropolitan Museum adds some further insights:

“In the rich heritage of monstrous beings that fell to the Sasanians when, at the beginning of the third century A.D., they became the masters of the Near Eastern kingdoms, there is little evidence of one demon who was to become a favorite during the three hundred years of Sasan- ian domination. A very ornate example of this creature, the senmurv, appears on a bronze plate (Figure 2) purchased last year by the Metropolitan Museum. The head is doglike, with open mouth displaying a forked tongue and a row of pointed teeth. The forelegs and paws are canine or feline, with sharp claws. The animal forepart then comes to an abrupt halt and the back half of the creature is a bird. Wings come from the shoulders and long slender feathers rise above the head. Finally a rich tail of double plumes curves out behind.

In the Avesta, the great book of the Zoroastrian religion that flourished in Iran from the Achaemenian through the Sasanian periods,from the fifth century B.C. to the seventh century A.D., there are a few references to a great bird, the saena, who was probably the senmurv. But our only real description of the creature comes from a collection of Pahlavi writings concerned with Zoroastrian mythology and compiled in the centuries after the fall of the Sasanian empire. The senmurv is said to be of three natures, and his actions are described thus: “The tree of all germs was produced, from which all species of plants continuously grow. And the senmurv has his resting place upon it; when he wanders forth from within it he scatters the dry seed into the water and it is rained back to the earth with the rain.”2 His service to mankind as the distributor of the seeds of plants is obviously a beneficent one, and this explains his frequent appearance in Sasanian art, in metal, stucco, stone, textiles- in all mediums except seals. The small stone stamp seals carved during the Sasanian period are varied in subject matter and show a number of composite creatures, but almost never the senmurv. This is hard to understand, since there is no question of either his popularity or his importance. In a seventh century rock relief at Taq-i-Bostan in western Iran he is carved on the garment worn by the king, and many fine textiles of the Sasanian period which were worn by nobles or used as hangings in the royal court are decorated with medallions each enclosing a senmurv.

The lion-griffin and the serpent-dragon are similar in many ways to the senmurv, but the feathered ending of the latter, the purely bird- like termination of his body, is not to be found in any of the animal conglomerates known from the heart of the ancient Near East, Iraq, or Iran.

Probably the first true prototypes of the sen- murv came from the art of the nomads who spread westward across the Russian steppes in the beginning of the first millennium B.C. and infiltrated the lands on the northern borders of these ancient civilizations. The Scythians appeared in the seventh century B.C. around the shores of the Black Sea and in the Caucasus between the Black and Caspian Seas. Their art was rich in fantastic animal-bird combinations, often including forms that were taken over from the Near East and elaborated by the native artists. Imagination, fantasy, and a distinct taste for the decorative are all characteristics of the style they developed while they were in touch with the cultures of the Near East. It is here that the closest parallels to the senmurv appear from the fifth century B.C. onward. The variety characteristic of both the animal and bird parts in these early examples disappears by the time of the Sasanian empire and the form becomes relatively standardized.” —The Senmurv

Some tentative conclusions may be made here:

- There appears to be strong linguistic relatedness in the etymologies of the Simorghian-Saena-Samrug(k)-Senmuruy-Semurg-Simurgh cognates from Central to West Asia…as well as to East Asia at the other extreme end of the Silk Road.

- The Turkic-Hun-Mongols were nomads with a central role in the transporting and the trading of silks, textiles from China To the West. The mythical bird is a motif found in silks and woven textiles also found in the mythology of the Turkic peoples of Central Asia, which is an indigenous form called Kerkés, thought to closely connected to the Indo-Iranian (perhaps proto-Indo-European) derivative Semrug, Semurg, Samran, and Samruk. The diffusion of the Simurgh-Phoenix motif took place along the Silk Road trails.

- The Persian-Greek Simurghs-Phoenixes forms are often said to be derived from the Egyptian Benu sunbird (or the Ba of Ra bird) and this has been accepted as truth without much detailed discussion(Herodotus attributes the phoenix’s origins to the Arabs rather to the Egyptians), nevertheless, we intend to reexamine this assumed derivation and source. We see no reason why the European and West Asian phoenixes could not have been derived from an Eastern source and/other Central Asian sources as well, as a result of the vast Sassanid and Persian and extensive Eurasian Silk Road trade routes. The West Asian griffin-like birds that often change and assume forms as part dog- or lion- or bat-forms rather than birds, appear to be late-comers (griffin metalwork forms also appear in a more eastern location in the Altai mountains in Scythian burials) … later than the West Asian Persian-Turkic eagle-motifs or the more heron-like slender forms from China/East Asia. … Cina / Sina was an ancient appellation and pre-fix for China [Sina (Chinese 支那), old Chinese form of the Sanskrit name Cina (चीन)] See Geoff Wade’s “The Polity of Yelang and the Origin of the Name ‘China’“, Sino-Platonic Papers, No. 188, May 2009], so that one would have thought it reasonable to posit that Sina-mru or Cinamros indicated a provenance from China or even the vague eastern region where the ancients thought China lay. There may have also have been two or more distinct forms of West vs. Eastern birds before their properties became conflated into the more prominent Simorghian or proto-Phoenix forms.]

- The Simurgh is seen as withering the tree in the Bundishne… i.e. scorching the tree and therefore associated with the sun. Therefore, the Simurgh may have been the origin of the Phoenix as Sunbird, however Matteo Compareti is of the view that the Senmurv shows up rather late in history — the evolution of the Phoenix as a Sunbird and Solar Symbol may have radiated from a centre in Central Asia, or even more easterly location as follows:

—>In West Asia, Semrug, Semurg

—-> Earlier Sēnmuruγ –>Middle Persian Pahlavi sēnmurw.

——>in Middle Persian Pāzand as Sīna-mrū. (si is said to mean “thirty”, bird seen as large as thirty hands, and of thirty colours) but Sina is a word often used in association with China, and therefore, the origin of the Sina-mru is likely a bird that came from the East.

Association with the Tree of Life

The evolution of the phoenix as a fertility and healing symbol (eagle) at the top of the Hom Tree.

Iranian legends consider the bird so old that it had seen the destruction of the world three times over. The Simurgh learned so much by living so long that it is thought to possess the knowledge of all the ages. In one legend, the Simurgh was said to live 1,700 years before plunging itself into flames (much like the phoenix).

The Simurgh was considered to purify the land and waters and hence bestow fertility. The creature represented the union between the Earth and the sky, serving as mediator and messenger between the two. The Simurgh roosted in Gaokerena, the Hōm (Avestan: Haoma) Tree of Life, which stands in the middle of the world sea Vourukhasa. The plant is potent, life-giving, medicinal and is called all-healing, the seeds of all plants are deposited on the Hom tree … seeds that cure all the illnesses of mankind.

The association with the Hom, results in another variant name for the bird, Homa or Huma which has a Persian origin, and which also reflected in Avestan Humāya.

—-> Early diffusion of bird on top of tree motif into northern and western China as the Feng-huang niao atop the Paulawnia tree, its adoption as one of the Four Directional Guardian Deities, is common throughout East Asia, as a result of the Han dynasty’s influence, as well as Hun-Mongolic movements on the continent.

In the Mēnōg ī Xrad (ed. Anklesaria, 61.37-41) the Sēnmurw’s nest is on the “tree without evil and of many seeds.” When the bird rises, a thousand shoots grow from the tree, and when he (or she) alights, he breaks a thousand shoots and lets the seeds drop from them.

From the Persian: As the seeds floated around the world on the winds of Vayu-Vata and the rains of Tishtrya cosmological motif developed and diffused eastwards on the Silk Road [… This corresponds to the Chinese phoenix’s role as the Heaven descended bird.]

For the worshipper, fortune/glory “around the house of the worshipper, for wealth in cattle, like the great bird Saena, and as the watery clouds cover the great mountains” (Yasht 14.41, cf. the rains of Tishtrya above). Like the Simurgh, farrah is also associated with the waters of Vourukasha (Yasht 19.51,.56-57). In Yašt 12.17 Simorgh’s (Saēna’s) tree stands in the middle of the sea Vourukaša, it has good and potent medicine and is called all-healing, and the seeds of all plants are deposited on it. — Encyclopedia Iranica’s “Simorg”

–> Did the Ho-o Bird in Japan originate from the source of the Hom? Homa? Huma? Hol? Or from the indigenous Ho-musubi (fire) deity

(—-> Feng-hom –> Feng-huang?)

The relationship between the Simurgh and Hōm is extremely close for Iranians, and especially in Zoroastrianism. Like the simurgh, Hōm is represented as a bird, a messenger of god, and the essence of purity that can heal any illness or wound. Hōm – appointed as the first priest – is the essence of divinity, a property it shares with the Simurgh. The Hōm is in addition the vehicle of farr(ah) (MP: khwarrah, Avestan: khvarenah, kavaēm kharēno) (“divine glory” or “fortune”). Farrah in turn represents the divine mandate that was the foundation of a king’s authority.

The Simurgh-Phoenix is a Symbol of Investiture It appears as a bird resting on the head or shoulder of would-be kings and clerics, for Iranians indicated Ormuzd’s acceptance of that individual as his divine representative on Earth; Falconry had already developed as a trademark sport of nomadic chieftain kings throughout Hunnic Eurasia and the Persian and Chinese royalty, and a legacy seen in medieval European royalty. The sport arrived in Korea and Japan, soon after the arrival of kurgan-tumuli building and horse-riding elite chieftain immigrants. In Korea and Japan, the phoenix’s association with Hom tree shows evident strong influences from the Chinese Han dynasty as well as of Iranian or Persian ones, due to Silk Road exchanges and trading activities.

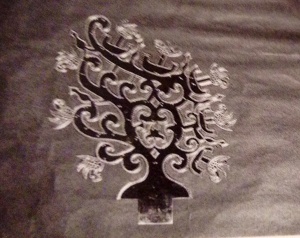

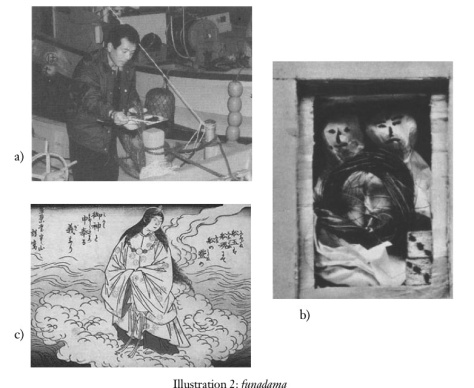

Reconstruction of fine filigree-work on a gilt crown with a tree and bird motif in a Japanese tumuli of the Kofun period

—–> At the same time, the “bird-alighting on the shoulder of the anointed king” concept is known to be one that is especially significant for the chiefdoms deriving legitimacy as royal lineages on the Korean peninsula, hence the identification of Korean kings (and queens in earlier times) with the Phoenix (see Phoenix Throne of Korea). The idea of a bird as a messenger of the Sky God or sky deities, becomes a cornerstone of the myths of divine kingship or heavenly descent in East Asia, and sacred birds feature prominently in many court-chronicled myths as well as folklore surrounding the royals of Korea and Japan. Genetically and culturally, the Koreans (and certain Korean lineage-related Japanese) are closely related to ancient North and Northeast Asian populations. Given that Jewish or Hebrew communities were known to have existed in various parts of China like Kaifeng, Luoyang and elsewhere in South China, we also cannot discount the intriguing possibility that the Japanese phoenix called Ho-o may be derived from a source connected to Jewish (or Jewish-Iranian) priestly lineages — the Rabbis called the phoenix the hol phoenix, the closest etymology for the Japanese phoenix so far (although hom is a another close cognate) … and there are those who have speculated that the danjiri resembles the holy ark of the Jews.

“The Talmudic version goes like this:”The Talmud tells how the phoenix (Hol) was the only animal allowed to stay in the Garden of Eden, because it refused to eat the forbidden apple. God granted the bird immortality for its obedience.” – “The phoenix through the ages”

A pair phoenixes adorn the rooftops of the mikoshi- danjiri deity carrier during a festival in Takayama, Gifu prefecture.

Identification of the phoenix with which bird? Eagle? Rooster?

According to Encyclopedia Iranica, with a very large, three-fingered bird, probably the Golden Eagle, on account of its being also the bird identified with the constellation Aquila.

The Fenghuang of the Chinese, said to live atop the Kunlun mountains, is also called the “August Rooster” (Chinese: 鶤雞; pinyin: kūnjī) with solar symbolism as an animal signalling the dawn sun and since it sometimes takes the place of the Rooster in the Chinese zodiac (although its features have evolved to comprise the composite features of six celestial beast over time) It is a symbol with positive connotations, symbolic of high virtue, grace and prosperity, associated with rulership like its Central Asian counterparts. The Chinese feng-huang was also often portrayed as a male-female yin-yang pair of birds, with the female being an emblem for the Empress. The Chinese regard the phoenix as a rare phenomenon (like its counterparts elsewhere) seen only in times of peace, and symbolizing conjugal bliss. — see Archetypes and Motifs in Folklore and Literature, by Jane Garry, Hasan El-Shamy. Charles Saba’s comparative writings on astrological charts and numerology establishes that Chinese astrology, zodiac and numerology systems were deeply influenced and fundamentally based on Chaldean sources (as were Greek, Indian Vedic and Egyptian ones):

“According to Chinese scholars, astrology was introduced in 2637 BC, as a result of the commercial trade between Emperor Huang Ti and the Chaldean Royalty. These origins made Chinese astrology primarily and deeply based on Numerology.

There are striking similarities between Chinese, Chaldean and Egyptian astrology, which goes beyond the use of 28 hsui and 12 animal types, as in the case between the Chinese Lunar Mansions and the Egyptian Lunar Mansion system.

The same occurs between the predictions of the Shih Chi (historical record) of Ssuma Chien, and the Chaldean ‘Enuma Anu Enlil’. These predictions, deal with the rising of the planets, their conjunctions and paths through the stars. It is strong enough to suggest that communication between the Chinese and Chaldean astrologers existed long before 1000 BC.

The newly acquired Chaldean astronomical sciences were translated into Chinese, and were imbued with the Chinese philosophical thought and influences. The numerological basis of Chinese astrology lies in the use of a specialized numbering system that counts from 1 to 60.

Since the general public is less familiar with this system, additional information will follow to provide a more comprehensive overview.

The numbers in this system consist of a first digit, from a series of ten ‘Heaven Stems’ (Tiangan), and the second from a series of twelve “Earth Branches” (Dìzhi).

The numbering system of 60 is used to count days, years and hours, thus arranging time into sixty-unit ‘cycles’, repeating it into the infinite past and future. Each year is numberedin an ever repeating 60-element cycle. So is each month, day, and hour.

Similarly, Heaven Stems and Earth Branches provided a progression of spaces in the circle of the horizon (each pair corresponding to 6 degrees in the western division of a circle into 360 degrees). Thus space and time could both be associated with units of measurement.

There are three systems used for counting and classifying the years: The Ten Heavenly Stems, the Twelve Earthly Branches(12 animals), and the Five Elements. The year of birth indicates a certain phase or aspect of a sixty-year cycle of time.

All throughout this process, is the ever present concept of Yin and Yang. The terms given to the complementary, dynamic forces that keep the universe in balance at every level.

In event predictions, hours, days, and years are associated with some pairs of Heaven Stems and Earth Branches, and depending on the combination, may be considered to be favorable or unfavorable for various activities, especially for people born at hours, days, or years associated with other combinations of Heaven Stems and Earth Branches.

Chinese astrology includes Five Elements instead of four: Fire, Earth, Metal, Water, Wood. They are agents or modifiers that subtlety alters the nature of whatever they represent.

There are ten Heaven Stems, and the pairs of Heaven Stems are aligned with the five elements and hence with various other significations connected with the ‘Five Elements’.

The significations associated with the ‘Five Elements’ range from flavors, colors, virtues, organs, and notes of the scale. Through the linkages between Heaven Stems and the Five Elements, time and direction was even more subtly linked with these other features of human experience.

Because there are ten Heaven Branches, and because the cycle is used to count years, the Heaven Branch is predictable from the western year. A Western year ending in 0 always corresponds to a Chinese G (Geng) year. Thus a Western year ending in 1 will be a Chinese H (Xin) year, a year ending in 2 an I (Rén) year, and so on.

The ancient Chinese use the 10 Heavenly Stems and 12 Earthly Branches, but the 12 animals were designated to equate to the 12 Earthly Branches in order remember them more easily.

Therefore, the twelve Earth Branches are aligned with the famous year animals used in Chinese astrology. But they are also associated with the constellations used in the West for signs of the zodiac, and with twelve Chinese hours of the day (each two hours long by international calculation), and with directions around the horizon.”

(The foregoing might lead us to infer a possible Middle or Near Eastern connection —> Feng-hom –> Feng-huang?)

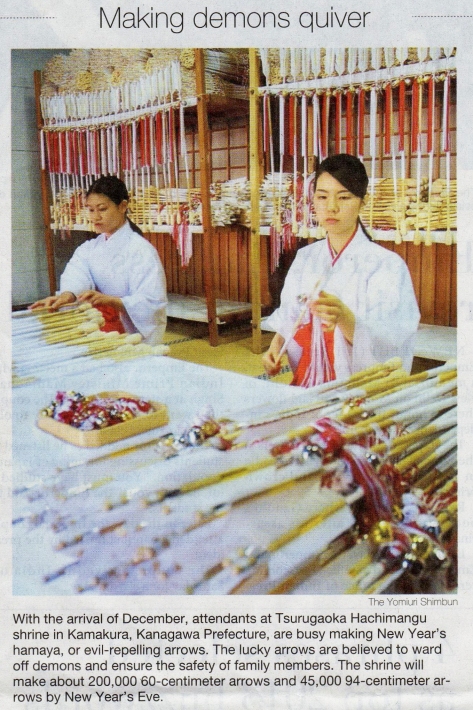

The Japanese rooster is associated with Amaterasu, and a Phoenix or Rooster often sits on top of the wooden cart or palanquin that carries the deity on procession about town from a shrine during a festival. This identification of the phoenix with another solar symbol and sunbird August-Rooster, suggests another intriguing connection — one with the Hepthalites (alternatively, Hata and Hatays from Hattusha or Nysa) … See Encyclopedia Iranica’s entry “Simorg”:

“The Sēnmurw is very prominent on the coinage of the Hephthalites in the seventh and eighth centuries C.E. It is distinguished from the standard Sasanian form by having rather a cock’s than a peacock’s tail and also frequently showing reptilian features, which are rare in the Sasanian form. Its head occurs as a crown-emblem in several issues (nos. 208-10, 241-243, 246, 254-255 in Göbl I, cf. the drawings in IV, pls. 6-7); in one issue (no. 259) the whole animal appears on the top of the crown. The head and neck, or the complete animal, are also used as countermarks (KM 102, 106, 107, 101, 106, 107, 101, 105, 3a-d, 11A-K, 1, 10 in Göbl II, 141ff., IV pl. 10). When carrying a pearl necklace in its mouth (Issue 255.1), the Sēnmurw is probably the conveyer of the investiture (Göbl, p. 156), whether the necklace can be identified with the xᵛarnah or not….

In the chapter on the classification of animals of the Bundahišn the three-fingered Sēn is called the largest of the birds (13.10), and also the Sēnmurw is of the species of birds (13.22); they are obviously identical. The three-fingered Sēn was created first among the birds, but is not the chief, a position held by the Karšipt (according to the Indian Bundahišn 24.11 a carg, falcon or hawk), the bird that brought the religion to the enclosure (var) of Jamšēd (cf. Vd. 2.42) (17.11). In 13.34-35 the Sēnmurw has come to the sea Frāxkard (Vourukaša) before all the other birds. In Zādspram 23.2 the Karšipt and the Sēnmurw are singled out among the birds to attend the conference with Ōhrmazd on the animals, the creatures protected by Wahman. Bundahišn 13 contains serious contradictions. While in 10 and 22 the Sēnmurw is a bird, … Zādspram 3.65 … counts … the Sēnmurw among the birds, though they are of a different nature, having teeth and feeding their young with milk from their breasts. Bundahišn 13.23 contradicts not only 10 and 22 but also 15.13, where the Sēnmurw is counted among the oviparous birds. From this state of affairs it can be inferred that there was an older version, in which the Sēnmurw was a bird pure and simple as in the Avesta, …..

An identification of the original Sēnmurw with a known bird is difficult. The Sēn’s being called three-fingered is puzzling, since most birds have four claws. Herzfeld (1930, pp. 142-43) suggested the ostrich, which has only three claws, but this is impossible because the ostrich is an African flightless bird. The epithet may then be based on the observation of the bird when perching on the branch of a tree when only three claws are visible. The Sēnmurw in representative art also has only three claws but, contrary to my earlier opinion (Schmidt, p. 59), it is hardly the source of the description. The three-fingered Sēn is the largest bird (Bundahišn 13.10) mentioned among the large birds, side by side with the eagle (āluh) and the lammergeier (dālman); this excludes the falcon, which is much smaller than either of them. In size and habitat the closest possibility would be the black vulture (Aigypius monachus), which nests mostly in trees, but as a scavenger does not hunt live prey. Therefore I would suggest the golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos), particularly if the identification with the constellation Aquila is correct. That the Simorḡ was not known solely as a mythological being, but also as a real bird, can be inferred from the fact that in Judeo-Persian the word translates the Hebrew näšär‘eagle’ (cf. Asmussen).” — Simorg

Born from an Golden Egg associations Turkic Kerkes tradition may be a close source or one of the underlying sources or provenance for the East Asian phoenix icon, particularly for Koreanic (Korean-descended Japanese lineages) because of King Suro of Gaya/Kaya and various Kim-Royal lineages of Silla, all said to be born from a golden egg, like the Turkic Kerkes which is…

“A Turkish version of the Phoenix and Bennu. It arises from a burning tree. It was at first represented by a wagtail but later it took the appearance of a heron with two long feather protruding from its head and red legs. It lived for 500 years and then at the end of its life it would be consumed in fire and was reborn as a golden egg to hatch again. It was the first creature to be created and it emerged from the primordial mud.” – See more here from mythicalcreatureslist.com

Here, in this connection, we bring the Greeks in, because they are said to have given the Phoenix the name of Circe, cognate with Kerkes.

“According to Greek mythology, the bird lives in Arabia, near a cool well. Every morning at dawn it bathes in the water and sings a beautiful song. So beautiful is the song, that the sun god would stop his chariot to listen.

The phoenix bird symbolizes immortality, resurrection and life after death. The Greeks probably got the idea from the ancient Egyptians. In ancient Greek and Egyptian mythology, it is associated with the sun god, the phoenix represented the sun, who dies in flames each evening and emerges anew each morning. The Arabs had an incombustible cloth woven of flexible asbestos that was thought to be its hair or plumage. There was only one phoenix at a time, and it lived for 500 years. It laid no eggs and had no young, and it was there when the world began. It was the quintessential firebird, young and strong” — khandro.net on “Rukh, Benne, Phoenix”

Recall that the earlier mentioned Kazakh Samruk (Uzbekistan) is also born from a golden egg. The Greek-Arab account of the Kerkes bird is however, strangely different in one respect from the Turkic Kerkes and the Kazakh Samruk … it lays no eggs. It is a self-contained, self-sufficient and the primordial sunbird. In all other accounts, phoenix eggs traditionally need fire in order to hatch.

Medieval mixed identities of the Simurgh:

Eagle and rain associations “The Armenian paskuc and the Georgian p’asgunǰi both translate the Greek gryps ‘gryphon, griffin’ in the Septuagint (Marr, p. 2083). It is also glossed as ‘bone-swallower’ (ossifrage, osprey) (Marr, p. 2087 n. 2), but also mentioned as a kind of eagle native to India. In Modern Armenian paskuč is the griffin vulture (Gyps fulvus). In Georgian sources ap’asgunǰi is described as having a body like that of a lion, head, beak, wings and feet like those of an eagle, and covered in down; some have four legs, some two; it carries off elephants and injures horses; others are like a very large eagle (Marr, p. 2083). In late mediaeval Georgian translations of the Šāh-nāma, Georgianp’asgunǰi renders the Persian simorḡ (Marr, p. 2085f.). In a Georgian parallel to the Armenian and Kurdish tales quoted earlier, the bird there called Sīnam and Sīmīr is replaced by p’asgunǰi (Levin-Schenkowitz, p. 1ff.). In a Talmudic tale a giant bird pwšqnṣʾ swallows the giant serpent that has swallowed a giant toad and settles on a very strong tree; Daniel Gershenson (personal communication) interprets this as a metaphor for the coming of the rainy season: the frog represents water, the snake drought, and the Pušqanṣā the rainy season. The tale is thus a reworking of the Sēnmurw story. Talmudic commentators identify the bird as a gigantic raven. In an illustration in the Gerona manuscript of Beatus’s commentary on the Book of Revelation, the picture of the Sēnmurw opposite that of an eagle is found with the subscript coreus (read corvus) et aquila in venatione “raven and eagle on the hunt” (Grabar, pl. XXVIII fig. 2). ***This evidence shows that the Sēnmurw took different shapes in different cultures and that the same name was used for real birds and fabulous composites as well as for benevolent and malevolent beasts.”***

Senmurw and Camros have starry associations The seasonal activity of the Sēnmurw in conjunction with Camrōš and Tištar can be interpreted consistently in astronomical terms. The symbolism of the Persian senmurw or Simurgh bird in astronomy and the pairing of stars/birds also influenced the dualist nature of the feng-huang, Chinese ideas about the peaceful and prosperous reign and sovereignty and Taoist cosmology and the meaning of the Chinese (East Asian) phoenix. The identity of Tištar with Sirius, the brightest star of the constellation Canis Major (the Great Dog), is well established, and it can be assumed that Sēnmurw and Camrōš are stars, too. For Sēnmurw the constellation Aquila (Eagle), or its most prominent star, Altair (Ar. al-ṭayr ’the bird’), is the most likely candidate. The heliacal rise of Sirius in July corresponds to the setting of Aquila. Camrōš may be identified with Cygnus (Swan), which sets some time after Aquila. The influence of Greek astronomy and astrology is well attested in Sasanian Iran, but itself goes back to Babylonian sources, and it is quite possible that the Avestan source was dependent on them (contra Schmidt, p. 10). The assumption that the rise of Tištar signals the beginning of the rains, as it does in Egypt, and must therefore be a direct borrowing, is not compatible with the climate of most of Iran. Historical ties between the Sassanian, Persian and Chinese empires are known.

Serpent/Dragon are enemies of the Simurgh From Azerbaijani folklore, we see that the dragon as enemy of the Simurgh-phoenix developed, adopted from a common source of cosmological knowledge as the Chinese idea of the Four compass directions -Four Guardian Deities, and the similar display of the oppositional pairing of the Feng-Huang and the dragon together, as mortal enemies.

The Simurgh and Phoenix is sometimes like a genie helping out a hero on his journey (sometimes in the Netherworld or a distant land. Derived from the Middle Persian and Iranian common stock of stories, Simurgh is transformed into “Sīmīr” in the Kurdish language. The scholar Trever quotes two Kurdish folktales about the bird. In one of the folk tales, a hero rescues Simurgh’s offspring by killing a snake that was crawling up the tree to feed upon them…introducing the Tree-and-Serpent-and-Bird Triad motif…a motif also seen in central and East Asia. As a reward, the Simurgh gives him three of her feathers which the hero can use to call for her help by burning them. Later, the hero uses the feathers, and the Simurgh carries him to a distant land. In the other tale, the Simurgh carries the hero out of the netherworld; here the Simurgh feeds its young with its teats, a trait which agrees with the description of the Simurgh in the Middle Persian book of Zdspram. In another tale, Simurgh feeds the hero on the journey.

The idea of the Phoenix emerging from the Worm /Silkworm in the ashes … probably diffused from the East, along the Silk Road, as a bird that resurrects itself, the Silkworm cocoon to butterflymoth to egg cocoon cycle, analogous to the Worm to Phoenix Cycle. With the idea of the resurrective power of the Phoenix, it becomes an important symbol of immortality, and appears on the mural walls of funerary tumuli of kings. The concept holds sway until Buddhist ideas of reincarnation take hold, and remains an important iconic symbol even thereafter. More below:

“In a Persian translation of Kazini’s Geography … we find this story, without the mention of a divine intervention but with explicit mention of the rain: when rain has fallen on the ashes of the Phoenix it gives rise to a work on with wings grow, and from this there develops a bird that lives and dies in the same way as its predecessor? In this last text it is especially clear that the rebirth of the bird is a consequence of the rain. The same perhaps finds expression in a Syriac text on the Phoenix that otherwise does not refer to the origin of the bird; Therefore there is moisture there, thanks to that kind of worm is born3. We shall have to go in some detail into the Judae-Christian conception of the developing the rain as the means by which God brings the dead to life4. This idea must also underly the motif of the rainfall on the ashes.

On the 3rd day it appears t o be a mature bird exactly like its predecessor … the detail of the life-inducing rain*probably received several Oriental version of the Physiologas: to be inferred from the Syriac text that is strongly dependent on the Physiologus, and Epiphanius’ version of the Phoenix myth clearly showing that he too was influenced by the world as indicated by this work, as indicated for instance by his mention of the period in which the worm develops in which the worm develops into a full-grown Phoenix.(*only found in the East)

Only the Physiologus and the texts related to it say that the worm developed into a Phoenix in 3 days. Most of the versions and translations state that the priest of Heliopolis examines the ashes on the altar on the morning after the burning and finds a worm. On the second day, the worm has acquired feathers and has become a young bird and on the third day, it appears to be a mature bird exactly like its predecessor” — Broek, “The Myth of the Phoenix”

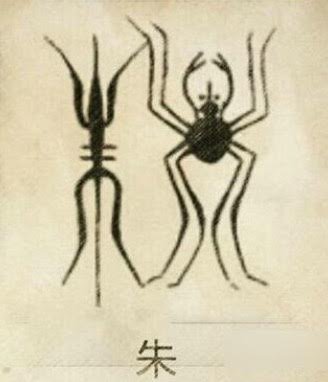

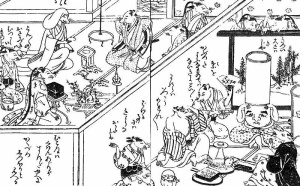

Four “worms” motif on a bronze mirror excavated from a Japanese tumuli of the Kofun period

Development of solar imagery, and the tradition of the self-immolating or self-combusting bird. According to several sources (Epiphanius, Zeno of Verona, Ambrose, Pseudo-Bede, but also the Turkish Kerkes tradition — the Phoenix causes itself to burst into flames after striking its wings together or spreading its wings.

We are also told in Broek’s book that…

“the Didascalia [Apostolum 40] stresses the fact that… the Phoenix makes a deep impression when it enters Egypt….It is also in this book that we first encounter the report that before setting itself afire, the phoenix faces the east and the rising sun, and then, utters a prayer.” Another suggestion here is that the phoenix is a foreign import, and a tradition from the east, is by Philostratus, who tells us that the Indians supplement the well-known singing dying Phoenix story by saying that like the dying swan, the Phoenix sings its own dirge as it is consumed in its nest.“

The Greek discourses and subsequent retellings of the Phoenix story have disseminated the motif to the rest of the Greco-Roman world and leaving a lasting literary and art legacy to the modern world today. A 2,500 year version went like this:

“The fabled bird is said to live 500 years or more, and when the old bird is tired, it flies from Arabia to land in Heliopolis, Egypt, the “City of the Sun.” There, it gathers cinnamon twigs and resin to build a nest of spices atop the Temple of the Sun. The sun ignites the nest and the old phoenix dies in flames. A new, young phoenix emerges from the ashes and wings back to Arabia to live another life cycle. The bird’s features have changed over the centuries, but most agree it’s an eagle-like bird with shining red, golden, and purple plumes.” – The Phoenix Through the Ages

The modern English noun phoenix is derived from Middle English phenix (before 1150), itself from Old English fēnix (around 750). Old English fēnix was borrowed from Medieval Latin phenix and, later, from Latin phoenīx, deriving from Greek φοίνιξ phóinīx. With the deciphering of the Linear B script in the 20th century, however, the ancestor of Greek φοίνιξ was confirmed in Mycenaean Greek po-ni-ke, suggesting a provenance in Hittite-Luwian Anatolia.

During the Classic period, the name of the bird, φοίνιξ, was variously associated with the color purple, ‘Phoenician’, and the date palm. According to an etymology offered by the 6th- and 7th-century archbishop Isidore of Seville, the name of the phoenix derived from its purple-red hue, an explanation that has been influential into the medieval world, and the bird was considered “the royal bird”.

Garden and magic apple associations In Azerbaijan, the Simurgh goes by the name of Zumrud (emerald). In an ancient tale about Malik Mammad, the son of one of the wealthiest kings of Azerbaijan, that king had a big garden. In the center of this garden was a magical apple tree that yielded apples every day. An ugly giant named Div stole all the apples every night. The king sent Malik Mammad and his elder brothers to fight the giant. In the course of this tale, Malik Mammad saves the Zumrud-Simurgh’s babies from a dragon. Slavic myths hav# variant, and the Russian “Firebird” folktale is now classified as Slavic which is in keeping with the results of genetic studies (#scroll down to the reference section)

Plant associations Through cultural assimilation the Simurgh was introduced to the middle East and Arabic-speaking world, where the concept was conflated with other Arabic mythical birds such as the Ghoghnus, a bird having some mythical relation with the date palm, and further developed as the Rukh (the origin of the English word “Roc“). In an illustration of a manuscript of the Thousand and One Nights the Simorḡ is identified with the monstrous bird Roḵ (cf. Casartellli, p. 82fIn Arabic translations of the Physiologus of Pseudo-Basil, twining vines and twigs of grape-vines, were a symbol of immortality that was associated with the Simurgh.

We can make one final observation, that the later the newcomers on the scene, such as the Slav settlers of the Siberian steppes, or the relatively late invaders of the Arab Islamic empire, the more likely the myths are to lose the mytheme of the phoenix as a beneficent provider of wealth, grace, immortality and divine legitimacy, and the more the likely these near-modern firebird myths will have a feature such as a garden with apples, a cultural folkhero or adventurer journeying very likely in the Underworld, elements introduced from other folktales as well as a more fantasaical and composite form of the phoenix beast, with body parts (such as its feathers that grant wishes) that are embued with magical charms or amulet powers, or other strange bestiary features.

Sources and further readings:

The Myth of the Phoenix: According to Classical and Early Christian Traditions. by R. Van den Broek, pp. 199-204

Hanns-Peter Schmidt,”Simorg” in Encyclopedia Iranica http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/simorg

The Phoenix Through the Ages” by Heather Shumaker, Swarthmore College bulletin, October 2008 http://media.swarthmore.edu/bulletin/?p=117

Simorgh, the fabulous mythological bird, Tehran Times, Sept 2012 http://www.tehrantimes.com/highlights/99516-simorgh-a-fabulous-mythological-bird

Feng-huang http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Feng-huang

Charles Saba’s writings on astrological charts, numerological systems and on “History: China” http://www.chsaba.com/history/china.html

#MOROVA, Irina et al. Russian ethnic history inferred from mitochondrial DNA diversity, American Journal of Physical Anthropology, Volume 147, Issue 3, pages 341–351, March 2012,

The 2012 study indicated that the core of the Russian gene pool is the mixture of two genetically different groups, the northern and southwestern, which are apparently related to the two major inflows of Slavic settlers from Western Europe to the East European Plain.

See Wikipedia entry’s “Firebird (Slavic) Folklore”: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Firebird_(Slavic_folklore)

The Senmurv http://www.metmuseum.org/pubs/bulletins/1/pdf/3257932.pdf.bannered.pdfv by Prudence Oliver Harpe

Magickal, Mystical Creatures: Invite Their Powers Into Your Life by D.J.ConwayThe so-called senmurv, an old Iranian theory reconsidered by Matteo Compareti

Senmurv silk fragments at the Victoria & Alberts

See fresco depiction of simurghs inside medallions (evoking motifs found on Sassanid textiles) in the church of Tigran Honents at Ani. P Donabedian and J. M. Thierry, Armenian Art, New York, 1989, p. 488.

In Cappadocia, Turkey, a row of simurghs are depicted inside the “Ağaçaltı” church in the Ihlara gorge. Thierry, N. and M., Nouvelles églises rupestres de Cappadoce, Paris, 1963, p. 84-85.

A. Jeroussalimskaja, “Soieries sassanides”, Splendeur des sassanides: l’empire perse entre Rome et la Chine (Brussels, 1993) pp. 114, 117f, points out that the spelling senmurv, is incorrect (noted by David Jacoby, “Silk Economics and Cross-Cultural Artistic Interaction: Byzantium, the Muslim World, and the Christian West”, Dumbarton Oaks Papers 58 (2004:197-240) p. 212 note 82.

Katsurano,Yamanashi prefecture, Middle Jōmon(2500-1500BC), Fuefuki City Board of Education

Katsurano,Yamanashi prefecture, Middle Jōmon(2500-1500BC), Fuefuki City Board of Education

![Relics of a bronze tree believed to be able to bring wealth unearthed from the Han Dynasty (202 BC - AD 220) family tombs in Guanghan city, China's Southwest Sichuan province, Oct 11, 2013.[Photo/CFP]](https://japanesemythology.files.wordpress.com/2014/07/image8.jpg?w=197&h=300)

The wani crocodile, as depicted in the Wakansansaizue. The illustration is borrowed from Wild in Japan’s excellent article:

The wani crocodile, as depicted in the Wakansansaizue. The illustration is borrowed from Wild in Japan’s excellent article: