Monguor (Wiki) http://www.thefullwiki.org/Monguor

The Monguor (Chinese: 蒙古尔), as known in the West, and Tu people (Chinese: 土族, also 土昆), White Mongol/Qagan Mongol (察罕蒙古尔) known in China are one of the 56 officially recognized ethnic groups in the People’s Republic of China. Their identity as “Tu Zu” was made by the Chinese Government in the first ethnic classificatory campaign carried out in 1953. Western scholars have long perceived the name to be derogatory, for it equated with “the indigenous peoples,” and used “Monguor” instead based on their self reference of “Chaghan Monguor” (or “White Mongols”, Mongolian: Цагаан Монгол).

They totaled 241,198 in the 2000 Census and were primarily distributed in Qinghai and Gansu provinces in the northwest. They speak an Altaic Mongolic language and practice sedentary agriculture supplemented by minimal animal husbandry. Their culture and social organizations are based on Confucianism, and their religion is a harmonious blend of the Yellow Sect (Tibetan) Buddhism, Taoism, and Shamanism.

Ethnic origins

Ethnically the “Monguor”/“Tu” are Xianbei, who could be characterized as the most powerful ethnic group who played significant roles in the Chinese and even the world’s history. They descended from the Donghu in northeast China more than 4,000 years ago and established extensive political establishments in China proper since the third century, whereby most of them were immersed into other peoples and classified into “Han” and other ethnic groups later. The “Monguor”/“Tu” represented the Xianbei who followed Tuyühu Khan to separate and undertake the great westward migration in the third century. After settling down in the northwest, they subjugated the native peoples who were summarily referred to as the “Qiang” and successively established the powerful empires of Tuyühu (often misspelled as Tuyuhun)(284-670), which annexed the Western Qin (385-431), Southern Liang (396-414), and Haolian Xia (407-431) kingdoms by the fifth century, and of Western Xia (1038-1227) through the thirteenth century. After the empires fell, they continued to play prominent roles in the national defense, and political and religious affairs of China, while preserving their language and culture attributable largely to their occupation in a unique and vitally strategic area in the northwest. Geographically, they have resided on the transitional areas from the Yellow Earth Plateau of China to the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Culturally and politically, they have occupied the frontier regions of the Chinese civilization on the east and Tibetan civilization on the west. The multi-ethnic environment and relatively distant distribution, detached from the political centers of China, enabled them to preserve their identity and culture until the present times.

Origins of the Chinese reference of “Tu”

The Chinese reference of “Tu” was derived from the name of Tuyühu Khan, who was the older son of the King of Murong Xianbei and separated to undertake the great westward migration from the northeast in 284. The last character of Tuyühu, pronounced as “hun” today, was pronounced as “hu” in the ancient Chinese language. The contemporary reference of his name spelled as “Tuyuhun” in China and the West should be “Tuyühu.” It came from the Chinese phonetic transcription of his original name “Teihu”,[1][2] which is still a common name seen among the Xianbei today. Since the Chinese language cannot represent “Tei,” two characters of “Tu” and “yü” were used. The ethnonym “Tu” in Chinese came from the abbreviation of “the Tuyühu people” or “the people of the Tuyühu Empire.” Between the years 908 and 1042, the reference became simplified into “Tuhu” and “Tüihu” people.[3][4] As the other ethnic groups of the Tuyühu Empire came to be ascribed with different ethnonyms through subsequent history, the Xianbei who founded the empire remained to bear with the identity of “Tu.”

Earliest record of the Chinese reference of “Tu”

The earliest record of the formal abbreviation of “Tu people” in Chinese occurred in the year of 1001 during the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127), when the Song officials discussed defense strategies against Western Xia.[5] Since its first inception occurred at a time of war conflict, the name “Tu” was most likely associated with not only a derogatory meaning, as Western scholars have perceived, but also a hostile undertone. Its overlap with “the indigenous peoples” was a coincidence. In the Chinese context, “the indigenous peoples” more often applied to the Chinese, especially the southern Chinese, who have been extensively conquered by the northern nomadic peoples. Unlike that in the West, a derogatory connotation for “the indigenous peoples” can hardly be perceived in China. Its derogatory undertone came from the concurrent meaning of the Chinese character “Tu” for “earth and soil.” That its first inception took place during the time of a war conflict between the two countries would make the interpretation of a derogatory and even hostile connotation stronger.

The ethnonym “Tu” is unsupported by ethnographic context. It had always been imposed upon them, never a self reference. In Huzhu County of Qinghai, which holds the largest Xianbei settlement, the commonest self reference is “Chaghan Monguor” (or “White Mongols”). It occurred in contrast to the Mongols, who were referred to as “Khara Monguor” (or “Black Mongols”), when the Mongols established political governance centered in Xining during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368). The Sanchuan/Guanting area in Minhe County has the most densely populated Xianbei settlement distributed on the north bank of the Yellow River, at the easternmost point of Qinghai, as the river flows eastward into Gansu. Archaeological discoveries[6] and historical research indicated that the area is the homeland of the legendary Emperor Yü the Great, who established the Xia Dynasty (2070 B.C.-1600 B.C.), the first ever recorded dynasty in the ancient Chinese history.[7][8][9][10] The dense settlement resulted from defense purposes against the Jin Dynasty (1115–1234) founded by the Jurchens, which overlooked Western Xia across the river. There the commonest self reference is “Dasni kung,” which literally means “the people of our ethnic group” and reflected their extensive occupation in the region. Up until recently, the area has existed very much like an independent kingdom, where everyone speaks their native Xianbei language, as an extension from the historical past that it had always been an important part of their empires for over seventeen hundred years. Since ethnic identities are formed when the outside members are encountered[11] and everyone who lived there has been Xianbei, there was no need to make ethnic distinctions among themselves. Because the Mongols did not establish political governance there during the Yuan Dynasty, they did not encounter the Mongols as the Huzhu and Datong Xianbei did. Therefore, no contrasting reference as “Chaghan” verses “Khara” Monguor was formed.

Origins of the Western reference of “Monguor”

The reference of “Monguor” in the Western publications came from their self reference as “Chaghan Monguor” (or “White Mongols”). It was derived from their origins from the Murong Xianbei, from whom Tuyühu Khan separated and who had been historically referred to as “the White Section,” or “Bai Bu,” due to their lighter skin.[12][13][14] The term “Monguor” was first used by the European Catholic missionaries, Smedt and Mosaert, who studied the Xianbei language and compiled a Xianbei-French dictionary in the beginning of the twentieth century.[15][16][17][18][19][20] Subsequently the Flemish Catholic missionary, Louis Schram, made it into an international name through three volumes of extensive reports based on his experiences from having living among them from 1911 to 1922.[21][22][23] The missionaries were well aware that the term was merely a variant pronunciation of “Mongol” in the Xianbei language, characterized by the final “-r” in place of “-l” in the Mongolian language.[24] Their insistence on using it resulted from an inadequate knowledge on the earlier history and culture of the Xianbei, and refusal to use the Chinese reference of “Tu” based on their interpretation that it was first used by the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) and was derogatory and inappropriate.

Despite that “Monguor” was made into an international name for the Xianbei, it is not representative: the reference is only used by the Xianbei in Huzhu and Datong counties in Qinghai, and when used, it should be combined with “Chaghan” (or “White”) in order to be distinguished from the “Khara” (or “Black”) Mongols. In Minhe County, which holds the most densely populated Xianbei settlement and where everyone speaks their native Xianbei language, it is never used as an autonym.

A brief history

Earliest origins: the Donghu (4,000 years ago-3rd Century)

Their earliest origins from the Donghu are reflected in their account of the unique wedding ceremony attributed to Madam Lushi,[25] who organized an ambush through an elaborate banquet combined with liquor and singing in order to subdue a bully named “Wang Mang”.[26][27][28][29][30] In historical terms, the “Wang Mang” people were recorded more than four thousand years ago as physically robust and active on the west of the present Liaoning, whose culture was associated with the Hongshan Culture.[31][32][33] In archaeological terms, the Hongshan Culture gradually gave rise to the Lower Xiajiadian Culture and represented the transition toward the bronze technology. It eventually evolved into the Upper Xiajidian Culture, which was associated with the Donghu and characterized by the practice of agriculture and animal husbandry supplemented by handicrafts and bronze art. The Donghu was a federation formed by the Mongolic-language speaking groups of the Donghu, Wuhuan, and Xianbei. Among the northern ethnic groups, the Donghu was the earliest to evolve into a state of civilization and first developed bronze technology. Through the usage of bronze weaponry and armored cavalry in warfare, they maintained extensive dominance over the Xiongnu on their west. In the end of the third century B.C., the Xiongnu Maodun attacked to destroy the Donghu by surprise and caused disintegration in the federation. The Wuhuan moved to Mt. Wuhuan and engaged in continuous warfare with the Xiongnu on the west and China on the south. The Donghu spoke Mongolic language and was formed by the federation of the Donghu, Wuhuan, and Xianbei.[34][35] As the Wuhuan and Xiongnu came to be worn out from the lengthy battles, the Xianbei preserved their strengths by moving northward to Mt. Xianbei. In the first century, the Xianbei defeated the Wuhuan and northern Xiongnu, and developed into a powerful state under the leadership of their elected Khan, Tanshihuai. In the third century, the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220A.D.) in China disintegrated into three kingdoms, including the Cao Wei (220-265) in the north, the Sun Wu (222-280) in the south, and the Shu Han (221-263) in the southwest. In 235, the Cao Wei assassinated the last Khan of the Xianbei, Kebineng, and caused disintegration in the Xianbei Kingdom. Thereafter, the Xianbei pushed their way inside the Great Wall and established extensive presence in China.

The Xianbei in China Proper (3rd century)

During the Sixteen Kingdoms (304-439) period, the Xianbei founded six kingdoms, including the Former Yan (281-370), Western Yan (384-394), Later Yan (383-407), Southern Yan (398-410), Western Qin (385-430) and Southern Liang (397-414). Most of them were unified by the Tuoba Xianbei, who established the Northern Wei (386-535), which was the first of the Northern Dynasties (386-581) founded by the Xianbei.[36][37][38] In 534, the Northern Wei split into an Eastern Wei (534-550) and a Western Wei (535-556). The former evolved into the Northern Qi (550-577), and the latter into the Northern Zhou (557-581), while the Southern Dynasties were pushed to the south of the Yangtze River. In 581, the Prime Minister of Northern Zhou, Yang Jian founded the Sui Dynasty (581-618). His son, Emperor Yang Guang, annihilated the Southern Chen (557-589), the last kingdom of the Southern Dynasties, thereby unifying northern and southern China. Yang Guang commanded the construction of the Grand Canal to enhance cultural exchanges and trade between the north and south, developed unified monetary and measurement standards, and initiated the national examination system to identify and promote talents based on merits.[39] After the Sui came to an end amidst peasant rebellions and renegade troops, his cousin, Li Shimin, founded the Tang Dynasty (618-907). Born in Qin’an, Gansu and revered as “the Heavenly Khan,” or “Tian kehan”,[40] Li led China to develop into the most prosperous state of civilization seen in the world, which saw extravagant palaces, architecture, music, literature, and fine arts, long before Europe was in the Dark Ages. The Khitans who founded the subsequent Liao Dynasty (916-1125) and the Mongols who founded the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) in China proper also derived their ancestries from the Xianbei. Through these extensive political establishments, the Xianbei who entered into China were immersed among the Chinese and later classified into “Han,” whereas the “Monguor”/”Tu” represented the Xianbei who have preserved their distinctive identity, language, and culture until today.

Separation from the Murong Xianbei and Westward Migration (4th century AD)

The separation of Tuyühu from the Murong Xianbei occurred during the Western Jin Dynasty (265-316), which succeeded the Cao Wei (220-265) in northern China. Legends accounted the separation to be due to a fight between his horses and those of his younger brother, Murong Wei. The actual cause was intense struggle over the Khanate position and disagreement over their future directions. The fraction that supported Murong Wei into the Khanate position aimed at ruling over China, whereas Tuyühu intended to preserve the Xianbei culture and lifestyles. The disagreement resulted in Tuyühu to proclaim as the Khan, or Kehan, and undertook the long westward journey under the title of the Prince of Jin, or Jin Wang, followed by other Xianbei and Wuhuan groups. While passing through western Liaoning and Mt. Bai, more Xianbei groups joined them from the Duan, Yuwen, and Bai sections. At the Hetao Plains near Ordos in Inner Mongolia, Tuyühu Khan led them to reside by Mt. Yin for over thirty years, as the Tuoba Xianbei and Northern Xianbei joined them through political and marriage alliances. After settling down in the northwest, they established the powerful Tuyühu Empire named to his honor as the first Khan who led them there, by subjugating the native peoples who were summarily referred to as the “Qiang” and included more than 100 different and loosely coordinated tribes that did not submitted to each other or any authorities.

After Tuyühu Khan departed from the northeast, Murong Wei composed an “Older Brother’s Song,” or “the Song of A Gan:” “A Gan” is Chinese transcription of “a ga” for “older brother” in the Xianbei language.[3][41] The song lamented his sadness and longing for Tuyühu. Legends accounted that Murong Wei often sang it until he died and the song got spread into central and northwest China. The Murong Xianbei whom he had led successively founded the Former Yan (281-370), Western Yan (384-394), Later Yan (383-407), and Southern Yan (398-410). Their territories encompassed the present Liaoning, Inner Mongolia, Shandong, Shanxi, Hebei, and Henan, and their capitals included Beijing and other cities. Through these establishments, they were immersed among the Chinese, whereas the Xianbei who followed Tuyühu Khan preserved their language and culture until the present times.

“Migration” of Mt. Xianbei from northeast to northwest China

In the extensive migrations that the Xianbei undertook in the northeast, northern, and northwest China, the name of Mt. Xianbei was found along their trajectories. The earliest recorded Mt. Xianbei was in the southern portions of Daxinganling, located in northeast Inner Mongolia, which represented the originating place of the Xianbei. Two Mt. Xianbei were recorded subsequently in western Liaoning: one in the present Jinzhou City and one near Yi County. Another Mt. Xianbei was recorded in the northern portions of Daxinganling, located near Alihe Town of Elunchun Autonomous County in Hulunbeiermeng in the northeastern portion of Inner Mongolia that borders eastern Russia. The Gaxian Cave,[42] currently Khabarovsk and Amur regions in the Russian Far East, which had stone inscriptions of the Northern Wei emperor dated 443, was recognized to be the sacred ancestral shrine of the Xianbei. In the northwest, the Qilian Mountains that run along Gansu and Qinghai provinces were referred to as the Greater Mt. Xianbei. In Sanchuan/Guanting of Minhe County in Qinghai, which holds the most densely populated Xianbei settlement, Mt. Xianbei stands in the west, upon which sits the ancestral shrine of the Xianbei Khans.

Tuyühu Empire (4th-7th centuries AD)

After Tuyühu Khan died in Linxia, also known as Huozhou, Gansu in 317, his sixty sons inherited to further develop the empire, by annihilating the Western Qin (385-430), which had annexed Southern Liang (396-414) earlier, and Haolian Xia (407-431) kingdoms, from which the Qinghai Xianbei, Tufa Xianbei, Qifu Xianbei and Haolian Xianbei joined them. These Xianbei groups formed the core of the Tuyühu Empire and numbered about 3.3 million at their peak. They carried out extensive military expeditions westward, reaching as far as Hetian in Xinjiang and the borders of Kashmir and Afghanistan, and established a vast empire that encompassed Qinghai, Gansu, Ningxia, northern Sichuan, eastern Shaanxi, southern Xinjiang, and most of Tibet, stretching 1,500 kilometers from the east to the west and 1,000 kilometers from the north to the south. They unified northwest China for the first time in history, developed the southern route of the Silk Road, and promoted cultural exchanges between the eastern and western territories, dominating the northwest for more than three and half centuries until the empire was destroyed by the Tibetans who rose up in 670.[43]

Origins of the English Reference of “Tibet”

Through this extensive rule, the Xianbei asserted everlasting cultural imprints in the region. The English reference for “Tibet” most likely came from the Xianbei language for the Tibetans referred to as “Tiebie,” in contrast to the self reference of the Tibetans as “Bo”.[44] The name “Tiebie” was probably derived from the Tuoba Xianbei who founded the Southern Liang (397-414). Because the Tuoba who established the Northern Wei (386-535) in China proper objected the Tuoba of Southern Liang to use the same Chinese characters, the latter adopted “Tufa,” when in fact they were of the same Tuoba descent.[45] After the Southern Liang was annexed by the Western Qin, which in turn was annexed by the Tuyühu Empire, the majority of Tufa Xianbei joined the Tuyühu Empire. Some submitted under the Northern Wei in China, while a small fraction went into Tibet and gave rise to the name “Tiebie”.[46] In the ancient Chinese records, the reference of Tibet included “Tubo” and “Tufan,” which reflected the Chinese transcriptions of “Tuoba” and “Tufa.” It is likely that “Tuoba” recorded in the Chinese language may have been pronounced as “Tiebie” originally in the Xianbei language. Among the Xianbei settlement in Minhe, Qinghai today, the La and Bao Family Villages were accounted to have descended from “Tiebie”,[47] indicating that they have derived their origins from the Tufa (Tuoba) Xianbei of the Southern Liang. The Tibetans refer to the Xianbei as “Huo’er,” which came from the final word of the name of Tuyühu Khan. The Xianbei refer to Tuyühu Khan as “Huozhou didi;” in which “Huozhou” was applied to Linxia, Gansu where Tuyühu Khan died, and “didi” was traditionally a reverence term for a deceased ancestor with deity status. The earliest record of the Xianbei in the Western publications was made by the French missionaries, Huc and Gabet, who traveled through northwest China in 1844-46. They used “Dschiahour” to represent the Xianbei, based on Tibetan reference,[48] in which “Dschia” was likely abbreviated from the first part of “Chaghan” (or “White”) from the self reference of the Xianbei as “Chaghan Monguor” (or “White Mongols”), and “Hour” was a variant record to the Tibetan reference of the Xianbei as “Huo’er” used by the Tibetans today.

The rise of Tibet and split of the Tuyühu Empire (7th century)

In the beginning of the Tang Dynasty, the Tuyühu Empire came to a gradual decline and was increasingly caught in the conflict between the Tang and Tibet. Because the Tuyühu Empire controlled the crucial trade routes between the east and the west, the Empire became the immediate target of invasion by the Tang. Meanwhile, Tibet developed rapidly under the leadership of Songzanganbu who united the Tibetans and expanded northward, directly threatening the Tuyühu Empire. The exile Tuyühu Khan, Dayan, submitted under Tibet, which resorted to an excuse that Tuyühu objected its marriage with the Tang and sent 200,000 troops to attack. The Tuyühu troops retreated to Qinghai, whereas Tibet went eastward to attack Dangxiang and reached into southern Gansu. The Tang government was shocked and sent five troops to fight. Although Tibet withdrew in response, the Tuyühu Empire lost much of its territory in southern Gansu. Meanwhile, the Tuyühu Government was split between the pro-Tang and pro-Tibet factions, with the latter increasingly becoming stronger and corroborated with Tibet to bring about an invasion. The Tang sent its famous general, Xue Rengui, to lead 100,000 troops to fight Tibet in Dafeichuan (present Gonghe County in Qinghai). They were annihilated by the ambush of 200,000 troops of Dayan and Tibet, which became the biggest debacle in the Tang history, and formally brought the Tuyühu Empire to an end.

After its fall in 670, the Tuyühu Empire split into an Eastern and Western Kingdom. The Eastern Kingdom existed on the eastern side of the Qilian Mountains and increasingly migrated eastward into central China, whereas the Western Kingdom existed under the leadership of the former exile Khan, Dayan, in Tibet. As the An Shi Rebellion shook up the Tang court and caused its emperor to flee, Tibet overtook the entire territory of Tuyühu until internal turmoil developed within the Tibetan government and massive revolts brought an end to its ruling. Through this period, the Xianbei underwent massive diasporas over a vast territory that stretched from the northwest into central and eastern parts of China, with the greatest concentrations found by Mt. Yin near Ordos. In 946, the Shatuo Turk, Liu Zhiyuan, conspired to murder the highest Xianbei leader, Bai Chengfu, who was reportedly so wealthy that “his horses had silver mangers”.[49] With the robbed wealth that included an abundance of property and thousands of fine horses, Liu established the Latter Han (947-950), which lasted only four years and became the shortest dynasty in the Chinese history. The incident took away the central leadership and stripped the opportunity for the Xianbei to restore the Tuyühu Empire.

Western Xia Empire (11th century)

The Western Xia Empire inherited the political and social structures of the Tang and further developed an outstanding civilization characterized as “shining and sparkling”.[50] It became the new kingdom for the Xianbei who had lost their country. The Western Xia made significant achievements in literature, art, music, architecture, and chemistry. Through effective military organizations that integrated cavalry, chariots, archery, shields, artillery (cannons carried on the back of camels), and amphibious troops for combats on the land and water,[51] the Xia army maintained a powerful stance in opposition to the Song, Liao (916-1125), and Jin (1115-1234) empires to its east, the last of which was founded by the Jurchens, who were the predecessors of the Manchus to found the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) later. The Xia territory encompassed the present Ningxia, Gansu, eastern Qinghai, northern Shaanxi, northeastern Xinjiang, southwest Inner Mongolia, and southernmost Outer Mongolia, measuring about 800,000 square kilometers.[52][53][54] In the beginning of the thirteenth century, Genghis Khan unified the northern grasslands of Mongolia and led the Mongol troops to carry out six rounds of attacks against Western Xia over a period of twenty two years. As Western Xia resisted vehemently, more and more Xianbei crossed the Qilian Mountains to join the earlier establishments in Qinghai and Gansu in order to avoid the Mongol assaults, which gave rise to the current settlements of the Xianbei. During the last round of the Mongol attacks, Genghis died in Western Xia. The official account of the Mongol history attributed his death to an illness, whereas legends accounted that he died from a wound inflicted in the battles. After the Xia capital was overrun in 1227, the Mongols inflicted devastating destruction on its architecture and written records, killing the last emperor and massacring tens of thousands of civilians. The Xia troops were later incorporated into the Mongol army in their subsequent military conquests in central and southern China. Due to the fierce resistance of the Xia against the Mongol attacks, especially in causing the death of Genghis, the Xianbei were initially suppressed in the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368). Toward the middle and later phases of the Yuan, they received equivalent treatment as the ruling Mongols and attained highest offices in the Central Court. After the Yuan fell, the Xianbei who followed the Mongols into the northern grassland were immersed among and later classified into the “Mongols.”

Origins of the English Reference of “Tangut-Xixia”

The English reference of “Tangut-Xixia” was derived from the combination of the Mongolian reference of “Tangut” and the Chinese reference as “Xixia” or “Western Xia.” The Chinese reference was derived from the location of the empire on the western side of the Yellow River, in contrast to the Liao (916-1125) and Jin on its east. The Mongolian usage of “Tangut” most likely referred to the “Donghu people;” “-t” in Mongolian language means “people”.[55][56] Whereas “Donghu” was a Chinese transcription, its Mongolian reference was “Tünghu”.[57] By the time that the Mongols emerged in the thirteenth century, the only “Donghu people” who existed were the Xianbei from Tuyühu Empire, then known as the “Tu” in Western Xia.

That the Mongols referred to Western Xia as “Tangut” to represent the founding ethnic group, the Xianbei, is consistent with the theories of the Mongol origins postulated by the Outer Mongolian scholars, who have held that the Mongols had descended from the Xiongnu, more specifically the eastern Xiongnu who spoke proto-Mongolic language, as opposed to the western Xiongnu who spoke proto-Turkish language. In contrast, the Chinese scholars have characterized that the Mongols had descended from the Xianbei. The Mongols were recorded as “Mengwu Shiwei” in the Northern Dynasties: “Mengwu” was a variant Chinese transcription of “Menggu” designated to the Mongols, and “Shiwei” was a variant transcription of the Xianbei, as “Xianbei” was also recorded as “Sian-pie,” “Serbi,” “Sirbi” and “Sirvi”.[58] This equated the Mongols to be “Mongol Xianbei,” which was likely associated with the submission of the Xiongnu under Xianbei. In 87 A.D., the Xianbei defeated the northern Xiongnu and killed their king, Chanyu Youliu, causing its thorough disintegration. Thereafter, the Xiongnu submitted under and self proclaimed to be Xianbei.[59] This resulted in a mix of the Xiongnu into Xianbei and made it difficult to differentiate the two groups in subsequent historical records. That the Mongolian term “Tangut” represented “the Donghu people,” the Xianbei who had founded the Tuyühu and Western Xia empires, would validate the theories of the Outer Mongolian scholars that the Mongols had descended from the Xiongnu. The fact that there were Wuhuan groups, who were part of the Donghu federation and followed Tuyühu Khan in the westward migration, would make the interpretation that “Tangut” represented “the Donghu people” stronger, not only from reflecting that the Wuhuan joined the Xianbei of the Tuyühu and Western Xia empires, but also contrasting that the Mongols had descended from the Xiongnu. If the Mongols had descended from the Xianbei, as the Chinese scholars characterized, the Mongols would have shared the same ethnic origins with the Xianbei of Tuyühu Empire and not have called them as “the Donghu people” in reference of Western Xia. While the intimate associations between the two groups were manifested in the cross references of the Mongols as “Mengwu Shiwei” (or “Mongol Xianbei”) from the first century and the Xianbei as “Chaghan (or White) Monguor” in the thirteenth century, ethnically and culturally they remained different. As much as the prefix “Mengwu” (or “Mongol”) in front of “Shiwei” (or “Xianbei”) marked the difference between the Mongols and the Xianbei, the prefix “Chaghan” in front of “Monguor” indicated that the Xianbei were not the same as the Mongols. Culturally, the Mongols have retained a nomadic lifestyle, whereas the social organizations and religious lives of the Xianbei are of far greater complexities.

Origins of the “Chaghan” (or “White”) Mongols, Khitans, and Jurchens

When the Mongols emerged as a mighty power in the thirteenth century, a reverse occurred in the ethnonyms of the Xianbei and Mongols. This was represented in the reference of the Xianbei as “Chaghan Monguor” (or “White Mongols”), which gave rise to the ethnonym of “Monguor” known in the Western publications. The term “White Mongols,” or “Bai Menggu,” first occurred when Genghis Khan united the Mongols to rise up in Mongolia in 1206. The Xianbei who resided near Mt. Yin self proclaimed to be “White Mongols” and joined them. They received the same treatment as the Mongols and partook in their westward conquests in Central Asia and Europe.[60]

As waves and waves of the Xianbei went south and westward to establish different empires, those who remained in the northeast emerged as major powers later to rule over China. While the “Mongol Xianbei” (or “Mengwu Shiwei”) emerged from the northern Manchuria and northeastern Mongolia, the Khitans, or “Qidan” in Chinese, derived their ancestral origins from the Yuwen Xianbei in southern Mongolia,[61] who had earlier founded the Western Wei (535-556) and Northern Zhou (557-581) of the Northern Dynasties. When the Khitans established the Liao Dynasty (916-1125) in China proper, they were referred to as “Qara (or Black) Khitāy”.[62] Their rule gave rise to the reference of China known as “Hătāi” and “Cathay” in the Persian and European countries.[63] The reference of “Qara” (or “Black”) as a prefix in the name of the Khitans and “Khara” (or “Black”) in that of the Mongols may indicate that both groups had substantial input from the Xiongnu, who by self proclaiming to be “Xianbei” earlier made it hard in distinguish in the Chinese records.

After the Xianbei vacated from the northeast, the Jurchens, known as “Nüzhen” in Chinese, moved southward into Manchuria from their original habitation in the Tungus Plains in eastern Russia located on the north of Manchuria. They occupied the former areas of the Xianbei and ascribed Mt. Xianbei with a new name, known as “Daxinganling,” which remains to be used today and literally meant “White Mountains” in their Tungus language.[64] They first established the Jin Dynasty (1115-1234) in northern China by pushing the Liao Empire of the Khitans westward into Xinjiang. After the Jin Empire was destroyed by the Mongols in 1234, they withdrew back to Manchuria and returned later with the rejoined forces from the Mongols to establish the last dynasty of the Qing (1644-1912) in China under the new ethnonym of Manchu, or “Man Zu” in Chinese.

Origins of the Xia Title: “the Great Xia Kingdom of the White and Mighty”

The full national title of Western Xia was “the Great Xia Kingdom of the White and Mighty,” or “Bai Gao Da Xia Guo” (白高大夏国). The term “White” (or “Bai”) was designated to the founding ethnic group, the Xianbei from the Tuyühu Empire, which is consistent with their reference of “Chaghan” (or “White”), derived from their origins from the Murong Xianbei known as the “White Section.” The term “Mighty” (or “Gao”) was designated to the “Qiang” people who formed the majority of the population. The “Qiang” were the native peoples who were subjugated by the Xianbei in the northwest. They initially rebelled but later their fate became intimately associated with the Xianbei, as they actively defended the empire when the enemies attacked. In addition to the Tibetans and authentic Han people, the “Qiang” comprised a portion of the Miao/Hmong who were relocated to the northwest from central China after their Three Miao Kingdom was destroyed by the legendary Chinese Emperor Yü the Great about four thousand years ago.[65][66] The “Qiang” referred to Western Xia as their “Gao (or ‘Mighty’) Mi Yao” Kingdom.[67] When “Mi Yao” is pronounced together, it is similar to “Miao.” Since the autonyms of the Miao/Hmong include “Guoxiong”,[68] “Gaoxiong,” and “Gouxiong,” the character “Gao” (or “Mighty”) in the Xia national title could have derived as a variant abbreviation. “Bai Gao” in the national title was in turn used it to refer to the Yellow River, which had traditionally been referred to as the “Mother River” of China, known as “Mu Qin He,” that has nurtured their homeland.

More recent history

The Xianbei culture today evolved as extensions from the Donghu, Xianbei, Tuyühu, Tang Dynasty, and Western Xia. The Flemish Catholic missionary, Schram, who conducted extensive studies on the Xianbei culture for over ten years in the beginning of the last century, cited Comte de Lesdain,[69] who characterized the Xianbei culture as “the most authentic reminder … from which the Chinese sprung.”[70] This characterization reflected the Xianbei culture under their observation has embodied “a high civilization fortified by its own history and distinctive social structure”[71] developed by the Xianbei forefathers from their extensive rulings over China and preserved by the “Monguor”/“Tu.” As early as the Tuyühu period, Confucianism served as the core ideology to govern the country, and the Chinese Buddhism and Shamanism functioned as the principle religions. In Western Xia, Confucianism was further strengthened, and Taoism was made into the national religion along with Buddhism. As the Yellow Sect of Buddhism, also known as the Tibetan Buddhism, became prevalent in the northwest, their religious lives shifted from the Chinese toward Tibetan Buddhism. After Western Xia fell, its territory centered in Ningxia was fragmented by the successive establishments of Shaanxi, Gansu, and Qinghai provinces, which increasingly weakened the political and military powers of the Xianbei. Through the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1912) dynasties, the Xianbei continued to play important roles in the national defense, and political and religious affairs of China. Starting in the middle of the Ming Dynasty, the ranches of the Xianbei were taken into the state possession, and their horses became the subject of being drafted into the national army and looted by the Mongols from the north, resulting in the eventual shift of their lifestyles toward sedentary agriculture, supplemented by minimum animal husbandry, as the original Xianbei groups became settled into the form of different villages. In the last two centuries, the areas formerly occupied by the Xianbei were encroached upon by increasing inland Chinese migrations. Throughout this period, the Xianbei maintained a high degree of political autonomy and self governance under the local chiefdom system of Tusi.[72][73][74][75][76] the Xianbei troops led by their Tusi defended not only their own homeland but also joined the national army to participate in wars that took place as far as in eastern Liaoning, Shaanxi, Shanxi, Yunnan, Mongolia, and Dunhuang,[77] which progressively weakened their military power. Their political power came to the ultimate decline when the Tusi system was abolished in 1931, which exacerbated more Xianbei to lose their language. By the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, only about fifty thousand of the Xianbei have maintained to speak their language, primarily in Qinghai and Gansu. During the Chinese classificatory campaigns carried out in the 1950s, those who could no longer speak their language were classified into “Han,” those who could not speak their language but adopted the Islamic religion were classified into “Hui,” those who followed the Mongols into the northern grassland were classified into “Mongols,” and those who spoke their language and adopted the Islamic religion were classified into “Dongxiang,” “Bao’an,” and “Yügu,” the last of which represented the intermixture of the Xianbei and Sari Uigur.

Xianbei life and culture today

Most Xianbei in traditional village settlements today practice sedentary agriculture, supplemented by minimum animal husbandry. Those who have succeeded in the Chinese educational system take up positions in the government as high as the vice governor and bureau levels, and work in a wide range of academic, medical, business, and international fields. Some have made their ways to study and work in the West.

Religious practices

In most villages, a Buddhist temple and a Taoist shrine coexist. Almost all the temples and shrines seen today have been rebuilt in the last three decades, since they were invariably destroyed during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). While Buddhist monks are common in most villages, Taoist priests and shamans have become very few and serve the whole area. The Taoist priests take charge of diverse functions that include weddings, funerals, and looking after the shrines, whereas the shaman’s primary function is to serve as a trance medium during the Nadun celebration and sometimes illness management.[78][79][80] Local accounts indicated that there have been multiple Catholic churches constructed in the Xianbei areas in the past.[81] They were destroyed in early 1950s after the Communists took control and have not been rebuilt.

Characteristic festivals: Nadun and Anzhao

Distinctive Xianbei cultural events take place throughout the year. Whereas the common festival held during the Spring Festival is “Yangguo,” the most characteristic tradition is represented by Nadun that takes place in the end of the summer. Nadun resembles Nadam of the Mongols in name but are different in format and content. Both “Nadun” and “Nadam” are special nouns designated to an annual festival and reflect their shared origins from the Xianbei]who were recorded to have “one major gathering every spring for leisure and fun by river”.[82] Whereas the Mongolian Nadam preserved the nomadic features of horse race, wrestling, and archery, the Xianbei Nadun has encoded their history through masked dance performances and presents as an annual military drill combined with joyful celebrations of harvest.[83] Held by villages in turn along the Yellow River and circles through the entire Sanchuan/Guanting region in Minhe, the Nadun festival is inherently tied to agricultural work. It functions as the Xianbei form of “Thanksgiving” in the Western culture and expresses gratitude for an abundance of harvest blessed by Heaven referred to as “Tiangere.” The event lasts over two months, starting from the twelfth of the seventh month to the fifteenth of the ninth month by the Chinese lunar calendar, and spans for a total of 63 days, giving rise to its eponym as “the world’s longest festival”.[84][85][86] Among the Huzhu Xianbei, the characteristic traditional dance is “Anzhao.” Its name and styles bear resemblance to the “Andai” dance of the Mongols who live in Ordos, an area that has historically served as the transitional point for the Xianbei to move about in China.

Wedding songs: Daola

The traditional weddings of the Monguor are incomparable affairs embellished with elaborate rules of courtesy and appropriateness, in which hundreds of songs referred to as “daola” are sung for days and nights with great variations in melody and contents.[87][88] Wherever the Monguor go, their songs follow them and can be heard in parties, banquets, and gatherings in cities where they work, which have come to be known as their signature mark.

A rapidly vanishing culture

In an age of globalization and commercialism that have swept across China and most parts of the world, the traditional Tu or Monguor culture and language are under great threats of becoming extinct. The Nadun programs have increasingly become shortened in most villages, and traditional songs and proverbs are rapidly vanishing. These cultural traditions represent rare and valuable assets not only for the Mongour, but also for the world. Given their relatively small population size, it is beyond their capabilities to defend against the larger forces and protect their own culture. Greater international efforts are needed to help preserve the unique cultural heritage that they have handed down for thousands of years.http://www.thefullwiki.org/Monguor

::

The Daur http://www.thefullwiki.org/Daur#cite_ref-0

History

The Daur (Tagour) placed between the Nonni River and the Amur River on a 1734 French map. Yaxa was a Daurian town prior to its fall to Khabarov’s Russian raiders in 1651.

Genetically, the Daurs are descendants of the Khitan, as recent DNA analyses have proven.[1] In Qianlong Emperor’s “钦定《辽金元三史语解》” he retranslate “大贺”, a Khitan clan described in 《辽史》, as “达呼尔”. That’s the earliest theory claim Daurs are descendants of Khitans.

In the 1600s, some or all of the Daurs lived along the Shilka, upper Amur, and on the Zeya River. They thus gave their name to the region of Dauria, also called Transbaikal, now the area of Russia east of Lake Baikal.

When the Russian explorers and raiders arrived to the region in the early 1650 (notably, during Yerofei Khabarov’s 1651 raid), they would often see the Daur farmers burn their smaller villages and taking refuge in larger towns. When told by the Russians to submit to the rule of the Czar and to pay yasak (tribute), the Daurs would often refuse, saying that they already pay tribute to the Shunzhi Emperor (whose name the Russians recorded from the Daurs as Shamshakan).[2] The Cossacks would then attack, usually being able to take Daur towns with only small losses. For example, Khabarov reported that in 1651 he had only 4 of his Cossacks killed while storming the town of the Daur prince Guigudar (Гуйгударов городок) (other 45 Cossacks were wounded, but all were able to recover). Meanwhile the Cossacks reported killing 661 “Daurs big and small” at that town (of which, 427 during the storm itself), and taking 243 women and 118 children prisoners, as well as capturing 237 horse and 113 cattle.[2] The captured Daur town of Yaxa became the Russian town Albazin.

Facing the Russian expansion in the Amur region, between 1654 and 1656, during the reign of Shunzhi Emperor, the Daurs were forced to move southward and settle on the banks of the Nonni River, from where they were constantly conscripted to serve in the banner system of the Qing emperors.

When the Japanese invaded Manchuria in 1931, the Daurs carried out an intense resistance against them.

:::

^ Li Jinhui, DNA Match Solves Ancient Mystery, china.org.cn 08/02/2001.

DNA Match Solves Ancient Mystery http://china.org.cn/english/2001/Aug/16896.htm

At some time in ancient Chinese history a powerful nation—the Qidan in what is now Inner Mongolia—simply disappeared. Where did these people go? A question that has perplexed scholars for generations may now be solved thanks to DNA.

Researchers from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) and Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CAMS) and others from Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region have concluded that the modern-day Daur people have a genetic match to the Qidan of ancient China, making them possible descendants of the Qidan people.

One of 56 ethnic groups in China with a population of some 121,500, the Daur today mainly live in Inner Mongolia, Heilongjiang and Xinjiang where they traditionally have engaged in agriculture and hunting, but now also maintain their own industries.

Liu Fengzhu, a researcher with the Nationalities Research Institute of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences which first began using DNA technology in its research in 1995, in a recent telephone interview talked about the discovery.

The research team first identified Qidan tombs from inscriptions on memorial tablets. From the Yelu Yu family tombs, they extracted DNA from the skull and teeth as well as carpal bone from Qidan woman corpse. At the same time, blood samples of Daur, Ewenki, Mongol and Han people in Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region were collected. From the blood samples, the researchers extracted DNA.

After sequence testing, they concluded that people of Daur ethnic group are all descendants of Qidan nationality.

Researchers also found possible links to the Qidan in other regions. They collected blood samples of the people with surnames of A, Mang and Jiang and other ethnic groups in Yunnan Province, who previously had claimed themselves descendants of Qidan rather than the ethnic groups such as Blang and Yi with which they were categorized on the founding of the People’s Republic of China more than 50 years ago.

“We found that the people in Yunnan Province with surnames of A, Mang and Jiang have similar patrilineal origins with Daur, so we identified them as descendants of Qidan, too,” Liu said.

The more than 100,000 people with surnames of A, Mang and Jiang who live mainly in Baoshan and Ruili districts of southwest Yunnan were particularly pleased that the DNA test substantiated their earlier claims.

Qidan was a nomadic tribe in ancient north China, living on fishing and hunting. They came into power in the last years of the Tang Dynasty (618-907) as people from central uplands who brought with them advanced agricultural and manufacturing technologies. In the year 916, Yeluabaoji, the chief of the Qidan nationality, became the first emperor of the Qidan State. The Qidan created their own written characters and had an official name of “Liao Dynasty (916-1125),” when many ethnic groups banded together.

Records about the Qidan nationality suddenly stopped in the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), together with its culture, and what happened to them has remained a matter of speculation.

Liu Fengzhu believes the Qidan people were scattered through war, which explains the presence of their descendants in different areas of China. Liu said the Qidan, like many other groups, would have faced recruitment as soldiers by the Mongols in the Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368) as they established the Great Mongol Empire which stretched over Europe and Asia.

“Some continued to live in a big group, such as Daur, so they are preserved. Some were assimilated by the people where they came live, just like ice in the sea. But those in Yunnan Province managed to keep the memory of the original ethnic group.”

Actually, the fate of the Qidan is not so unusual, Liu said. Similar cases can be found among other minority groups. For example, some Uygur people (a major ethnic group of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region) now live in Taoyuan County of Hunan Province.

(china.org.cn by Li Jinhui 08/02/2001)

:::

Am J Phys Anthropol. 2007 Feb;132(2):285-91.

Molecular genetic analysis of Wanggu remains, Inner Mongolia, China.

Fu Y, Zhao H, Cui Y, Zhang Q, Xu X, Zhou H, Zhu H.

Source: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16634045

Ancient DNA Laboratory, Research Center for Chinese Frontier Archaeology, Jilin University, Changchun 130012, People’s Republic of China.

Abstract

The Wanggu tribe, which contributed significantly to the foundation of the Yuan Dynasty, was one of the groups living on the Mongolian steppes during the Jin-Yuan period (AD 1127-1368) of Chinese history. However, there has been both archaeological and historical dispute regarding the origin of the ancient tribe. Recently, we discovered human remains of the Wanggu tribe in the Chengbozi cemetery in the Siziwang Banner of Inner Mongolia, China. To investigate the genetic structure of the Wanggu tribe and to trace the origins of the tribe at a molecular level, we analyzed the control-region sequences and coding regions of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) from the remains by direct sequencing and restriction-fragment length polymorphism analysis. In combination with mtDNA data of 15 extant Eurasian populations, we performed phylogenetic analysis and multidimensional scaling analysis. Our results show that the genetic structure of the Wanggu tribe in the Jin-Yuan period is a complex matriline, containing admixture from both Asian and European populations. In addition, we reveal that on the basis of mtDNA data, the ancient tribe may share a recent common ancestor with the Turkic-speaking Uzbeks and Uighurs.

Copyright 2006 Wiley-Liss, Inc.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16634045

:::

Changchun Y, Li X, Xiaolei Z, Hui Z, Hong Z, Genetic analysis on Tuoba Xianbei remains excavated from Qilang Mountain Cemetery in Qahar Right Wing Middle Banner of Inner Mongolia. FEBS Lett. 2006 Nov 13;580(26):6242-6. Epub 2006 Oct 20.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17070809

.

Source

Ancient DNA Laboratory, Research Center for Chinese Frontier Archaeology, Jilin University, Changchun 130012, P.R. China.

Abstract

Sixteen sequences of the hypervariable segment I (HVS-I, 16039-16398) in mtDNA control region from ancient Tuoba Xianbei remains excavated from Qilang Mountain Cemetery were analyzed. In which, 13 haplotypes were found by 25 polymorphic sites. The haplotype diversity and nucleotide diversity were 0.98 and 0.0189, respectively, and the mean of nucleotide number differences was 6.25. Haplogroup analysis indicates these remains mainly belong to haplogroup C (31.25%) and D (43.75%). According to the published data were considered, we can suggest that the Tuoba Xianbei presented a close genetic affinity to Oroqen, Outer Mongolian and Ewenki populations, especially Oroqen.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17070809

:::

Yi Chuan, Genetic analyses on the affinities between Tuoba Xianbei and Xiongnu populations. 2007 Oct;29(10):1223-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17905712

Yu CC, Xie L, Zhang XL, Zhou H, Zhu H.

Source

College of Life Science, Jilin Normal University, Siping 136000, China. changchun-yu@tom.com

Abstract

7 mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) sequences from Tuoba Xianbei remains in Dong Han period were analyzed. Together with the Data of Xiongnu published, the genetic affinities between Tuoba Xianbei and Xiongnu were analyzed in genetic diversity, haplogroup status, Fst genetic distances, phylogenetic analysis and multidimentional scaling (MDS) analysis. The results indicated that the Tuoba Xianbei presented the closer affinities to the Xiongnu, which implied that there was the gene flow between Tuoba Xianbei and Xiongnu during the 2 southward migrations

:::

Am J Phys Anthropol. 2007 Nov;134(3):404-11.

Molecular genetic analysis of remains from Lamadong cemetery, Liaoning, China.

Wang H, Ge B, Mair VH, Cai D, Xie C, Zhang Q, Zhou H, Zhu H.

Source http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17632796

Ancient DNA Laboratory, Research Center for Chinese Frontier Archaeology, Jilin University, Changchun 130012, People’s Republic of China.

Abstract

The Xianbei existed as a remarkable nomadic tribe in northeastern China for three dynasties: the Han, Jin, and Northern-Southern dynasties (206 BC to 581 AD) in Chinese history. A very important subtribe of the Xianbei is the Murong Xianbei. To investigate the genetic structure of the Murong Xianbei population and to address its genetic relationships with other nomadic tribes at a molecular level, we analyzed the control region sequences and coding-region single nucleotide polymorphism markers of mtDNA from the remains of the Lamadong cemetery of the Three-Yan Culture of the Murong Xianbei population, which is dated to 1,600-1,700 years ago. By combining polymorphisms of the control region with those from the code region, we assigned 17 individuals to haplogroups B, C, D, F, G2a, Z, M, and J1b1. The frequencies of these haplogroups were compared with those of Asian populations and a multidimensional scaling graph was constructed to investigate relationships with other Asian populations. The results indicate that the genetic structure of the Lamadong population is very intricate; it has haplogroups prevalent in both the Eastern Asian and the Siberian populations, showing more affinity with the Eastern Asian populations. The present study also shows that the ancient nomadic tribes of Huns, Tuoba Xianbei, and Murong Xianbei have different maternal genetic structures and that there could have been some genetic exchange among them.

(c) 2007 Wiley-Liss, Inc.

:::

[Note: Hg G – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haplogroup_G_(mtDNA) It is an East Asian haplogroup.[4] Today, haplogroup G is found at its highest frequency in northeastern Siberia (Itelmens, Koryaks, etc.).[3] Haplogroup G is one of the most common mtDNA haplogroups among modern Japanese and Ainu people (as well as among people of the prehistoric Jōmon culture in Hokkaidō), and it is also found at lower frequency among some other populations of East Asia, Central Asia, Bangladesh,[citation needed] and Nepal. However, unlike other mitochondrial DNA haplogroups typical of populations of northeastern Asia, such as haplogroup A, haplogroup C, and haplogroup D, haplogroup G has not been found among indigenous peoples of the Americas.

Am J Phys Anthropol. 2009 Jan;138(1):23-9.

Ancient DNA analysis of human remains from the Upper Capital City of Kublai Khan.

Fu Y, Xie C, Xu X, Li C, Zhang Q, Zhou H, Zhu H.

Source http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18661472

Ancient DNA Laboratory, Research Center for Chinese Frontier Archaeology, Jilin University, Changchun, People’s Republic of China.

Abstract

Analysis of DNA from human archaeological remains is a powerful tool for reconstructing ancient events in human history. To help understand the origin of the inhabitants of Kublai Khan’s Upper Capital in Inner Mongolia, we analyzed mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) polymorphisms in 21 ancient individuals buried in the Zhenzishan cemetery of the Upper Capital. MtDNA coding and noncoding region polymorphisms identified in the ancient individuals were characteristic of the Asian mtDNA haplogroups A, B, N9a, C, D, Z, M7b, and M. Phylogenetic analysis of the ancient mtDNA sequences, and comparison with extant reference populations, revealed that the maternal lineages of the population buried in the Zhenzishan cemetery are of Asian origin and typical of present-day Han Chinese, despite the presence of typical European morphological features in several of the skeletons.

:::

Religions of the Silk Road http://depts.washington.edu/silkroad/exhibit/religion/religion.html

The Tuoba Xianbei and the Northern Wei Dynasty http://depts.washington.edu/silkroad/exhibit/nwei/essay.html

This exhibit was organized as part of Silk Road Seattle, a collaborative public education project exploring cultural interaction across Eurasia from the first century BCE to the sixteenth century CE. Silk Road Seattle is sponsored by the Walter Chapin Simpson Center for the Humanities at the University of Washington. Images of art objects are provided through the kind cooperation of museums and photographers around the world.

It is believed that the Tuoba Xianbei (also known as the Toba Wei and the Tabgatch) developed an independent cultural identity separating them from the larger cultural milieu of Eastern Hu peoples of northern China sometime in the first century BCE. No mention of the Xianbei appears in the annals of Chinese history until later, yet it is the Tuoba Xianbei’s own legends have helped to establish an approximate place of origin for this people. The Xianbei creation myth has their earliest ancestors emerging from a sacred cave, the location of which was lost to the Tuoba Xianbei themselves. According to the Weishu, the history of the Northern Wei dynasty later founded by the Tuoba Xianbei, in 443 CE a contingent of horsemen known as the Wuluohou asked for an audience with the Northern Wei emperor Tuoba Dao. They informed him that their people had heard of a cave located in what is now the Elunhchun Autonomous Banner in northeastern Inner Mongolia. The local inhabitants worshiped this cave as a Xianbei ancestral shrine, a fact that convinced Tuoba Dao that the legendary cave that gave birth to his people had been located. The Weishu goes on to say that the emperor sent an emissary, Li Chang, to investigate the report. Li Chang verified the story, and held various ceremonies to worship the Xianbei ancestors, and left an inscription describing the ceremonies. The cave, known today as Gaxian cave site, and the inscription were discovered in 1980 by archaeologists. This find and other historical and archaeological evidence has helped to verify that the Tuoba Xianbei probably emigrated south from this area sometime in the early first century CE.1

By the mid-third century CE, Xianbei controlled much of northern China, from Hebei and Shanxi to the Daqing Mountains in Inner Mongolia. In 258 a Xianbei confederation was formed, and a few decades later came to the aid of the Western Jin dynasty, who were under attack from an army led by a Liu Yuan, a man of Xiongnu descent who made an unsuccessful bid to reestablish the Xiongnu empire. As a reward, the Western Jin granted the Xianbei leader, Tuoba Yituo, a fiefdom and military rank. This, however, was not enough to put an end to Xiongnu ambitions. They sacked the Western Jin capital in 311 CE and established the brief reign later referred to in Chinese histories as the Former Qin.

The Former Qin court forcibly removed the Xianbei to Shandong province, removed their leader to their capital Changan as hostage, took away their herds and stationed troops that forced them to engage in agriculture. By the late 380s the Former Qin dynasty had effectively collapsed after a failed attempt to conquer southern China, and the hostage Xianbei leader, Tuoba Gui, took the opportunity to establish his own reign as King of the State of Wei in 386. In 398, with much of northern China was under his control, Tuoba Gui set up the capital of the Northern Wei empire of Pingcheng (modern Datong in Shaanxi).2 After repeated attacks from nomadic groups moving south from Outer Mongolia, in 429 the Northern Wei launched a decade-long military campaign, forcing the nomads to submit and effectively securing their northern border.

The Northern Wei dynasty proceeded to effectively rule what would become the longest-lived and most powerful of the northern empires prior to the reunification of northern and southern China under the Sui and Tang dynasties. Trade flourished between China and Central Asia, and the influence of Indian artistic styles is particularly evident in the art of the Northern Wei period. Like the Mongols a millennium later, the Xianbei came to rely heavily on Han Chinese administrators and bureaucrats to help run the state. This close contact with Chinese culture helped transform the Xianbei aristocratic class from nomadic horsemen to Sinophilic urbanites. Important and influential families (including the imperial family) adopted Chinese surnames, abandoned traditional dress for Chinese fashions, and perhaps most importantly for Chinese art history, converted to Buddhism, which they enthusiastically patronized.

Great wealth and large parcels of land were donated to Buddhist monasteries, which would later lead to a serious drain of capital and a real threat to the state. But for most of the fifth century, Buddhism received the virtually unrestrained support of the Northern Wei court, except during a brief period from 446 to 452, when the emperor Dai Wudi (423-452) made Daoism the religion of state, and brutally persecuted Buddhism and its clergy and monasteries, as well as its art, literature and architecture. Upon Wudi’s death, the persecution ended, and generous court sponsorship of Buddhism resumed. The highlight of this sponsorship is arguably the cave temples of Yungang, and the eclectic monumental icons that so clearly demonstrate the Northern Wei sculptural style.

While the sinicization of the Northern Wei rulers pleased the empire’s Chinese subjects, it alienated those Tuoba Xianbei who desired to retain their ethnic identity. Feeling abandoned by their own rulers in favor of Chinese subjects, compounded by the loss of capital through extravagant patronage of Buddhist culture, led to a military uprising in 524. A few years later, a full civil war exploded after the empress Hu had the emperor Xiao Mingdi assassinated in order to put her son on the throne. Both she and her child were killed in 534, and the empire was split into two halves, ruled by the Eastern and Western Wei dynasties, which would rule only for a number of decades until the establishment of the Sui dynasty in 589.

(1) Adam T. Kessler, Empires Beyond the Great Wall: The Heritage of Genghis Khan (Los Angeles: Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, 1993), pp. 70-73.

(2) Ibid, p. 81.

:::

The New Whites – Xianbei http://www.dandebat.dk/eng-dan14.htm

:::

Genetically, the Daurs are descendants of the Khitan, as recent DNA analyses have proven.[1] In the Qianlong Emperor’s “钦定《辽金元三史语解》” he retranslates “大贺”, a Khitan clan described in 《辽史》, as “达呼尔”. That’s the earliest theory claim Daurs are descendants of Khitans.

In the 17th century, some or all of the Daurs lived along the Shilka, upper Amur, and on the Zeya River. They thus gave their name to the region of Dauria, also called Transbaikal, now the area of Russia east of Lake Baikal.

By the mid-17th century, the Amur Daurs fell under the influence of the Manchus of the Qing Dynasty which crushed the resistance of Bombogor, leader of the Evenk-Daur Federation in 1640.Many Daurs are shamanists. Each clan has its own shaman in charge of all the important ceremonies in the lives of the Daur. However there are a significant number of Daurs who have taken up Lamaism (Tibetan Buddhism).

Gaxian Cave Site http://www1.chinaculture.org/library/2008-02/15/content_33489.htm

The Gaxian Cave Site is located 10 kilometers northwest of Alihe Town in the Oroqen Banner of the Hulunbair League in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region.

The site lies at the eastern foot of the northern peak of the Great Hinggan Mountains. The cave is located on a 100-meter-high granite peak and towers at about 25 meters. The mouth of the cave is shaped like a triangle 12 meters high and 19 meters wide. The cave contains a wide space stretching 92 meters from south to north, 27 to 28 meters east to west and reaching over 20 meters at its highest peak. It covers an area of over 2,000 square meters, resembling a grand hall. To the northwest is an oblique cave nine meters wide, six to seven meters high and 22 meters long. About 11 meters up in the east wall of the grand hall is a five-meter-wide cave that is over 10 meters deep. In the middle of the grand hall lies an irregular natural stone board about 3.5 meters in length and three meters wide, with a 0.5-meter-high stone supporting it that resembles a stone table.

Located about 15 meters to the west wall is a line of stone inscriptions containing 19 rows and 201 characters, written in a style typical of the Northern Dynasties (386-581). The discovery of the Gaxian Cave provides precious archaeological materials for study into the cultural origin of such ethnic groups as the Serbi. http://china-tour-guide.blogspot.jp/2006/12/protected-sites-gaxian-cave-site.html

A visit to Gaxian Cave, Inner Mongolia Society for East Asian Archaeology (SEAA) – EAANnouncements 15

by Juha Janhunen

Gaxian Cave is located in the Da Xing’an Range, 10 km northwest of Alihe (the administrative center of the Oroqen Autonomous Banner) in northern Inner Mongolia. This cave, whose southwest facing entrance is easily accessible from a small fluvial plain ten meters below, is 120 m deep and 22 m high. The surrounding landscape is covered by Manchurian primeval forest. No other comparable caves exist in the vicinity.

In recent history, Gaxian Cave is known to have been used as an occasional shelter by Tungusic-speaking Oroqen hunters, the original inhabitants of the region. However, the cave seems to be both large and old enough to have been occupied since Palaeolithic times. Study of the cave was initiated in 1980 by Prof. MI Wenping, a prominent specialist on Manchurian archaeology and history. On his fourth visit to the cave, he located on the wall close to the entrance an inscription comprising 201 Chinese characters. This inscription, which contains a date equivalent to A.D. 443, was soon found to be almost identical to a passage in the Wei Shu, the dynastic history of the Northern Wei empire (A.D. 386-534). The passage records a mission sent by the Wei emperor to visit an ancestral ‘temple’ in his tribal homeland. Gaxian Cave may have been this ‘temple’. The ethnic group that established the Northern Wei empire is known historically as Tabgach (Tuoba) and thought to be the descendant of the Sienpi (Xianbei), both of which are believed to have been linguistically related to the later Mongols. Gaxian Cave thus provides tantalizing perspectives on early ethnic migrations in protohistoric Manchuria and Mongolia.

After first interviewing Prof. Mi in Hailar, the capital of the prefecture, I made a visit to Gaxian Cave in late June 1994. The cave, which is currently being developed as a local tourist site, attracts few foreign visitors. The objectives of my visit were to form a good understanding of the site as well as an opinion concerning the authenticity of the inscription. Although only the microscopic and chemical analysis of the rock surface can possibly provide a definitive answer regarding the latter, my own visual assessment leads me to support the established dating of the inscription. As for the overall archaeological potential of Gaxian Cave, it can hardly be exaggerated.

It is unfortunate that very little was done following the initial survey. A 1 x 20 m trench excavated by Prof. Mi and his team represents less than 2 of the total floor area. It has yielded a small number of man-made objects which are today exhibited at the museum in Hailar, including late Palaeolithic stone tools, Neolithic vessels and bone artifacts, as well as objects dating to medieval and modern times. Bones of wild mammals were also found in abundance.

Although there seems to be considerable local interest in continuing the research at the site, the archaeological authorities in Beijing seem to have taken the stand that the available financial resources and technological know-how do not yet allow for a comprehensive multidisciplinary investigation of Gaxian Cave. In view of the obvious regional significance of the site, this might be a case for an international project in which some of the neighboring countries, notably Korea and Japan, could perhaps participate.

(Note: Please contact the author for references)

Dept. of Asian and African Studies, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland

:::

Gaxian Cave – Show Caves of China

Gaxian Cave is located at the eastern foot of the Great Hinggan Mountains in the Da Xing’an Range. The southwest facing entrance is easily accessible from a small fluvial plain ten meters below. The portal is shaped like a triangle 12m high and 19m wide. Located in a 100-metre-high granite peak the huge chamber is 92m long from south to north and 28m wide, which sums to about 2,000m². The ceiling is up to 22m high. In the east wall is a side branch, starting 11m above ground, which is 5m wide and 10m deep.

The cave is almost empty, but with a comfortable almost flat dirt floor, which makes it a good shelter an meeting place. In the middle of the chamber lies an irregular natural stone plate, about 3.5m by 3m, resembling a rock table. It is supported by a half metre high stone.

The cave has been occupied since Palaeolithic times. The first exploration was undertaken by Prof. Mi Wenping, a prominent specialist on Manchurian archaeology and history. He discovered an engraving at the west wall showing 19 lines and 201 characters, in a style typical for the Northern Wei empire (386-581). It was a passage from the Wei Shu, the dynastic history, telling about a mission sent by the Wei emperor to visit an ancestral temple in his tribal homeland, probably a reference that Gaxian Cave may have been this temple. It also contains a date, which equivalents the year 443.

Until now only very little arcjaeolig research has been made. There has been one excavation of a 1m x 20m trench by Prof. Mi and his team, which equals about 2% of the total floor area. But the results are impressive, a number of man-made objects which are today exhibited at the museum in Hailar, late Palaeolithic stone tools, Neolithic vessels and bone artifacts. There have been numerous palaeontolic remains, especially bones of wild mammals. Medieval and modern time artifacts have been discovered too.

Gaxian Cave is extraordinary, as no other comparable caves exist in the vicinity. The geology is not suitable for the formation of caves. Concerning the sources we have, we guess it is a tectonic cave, but we do not really know.

:::

The following is excerpted from The new whites – Xianbei

Xianbei was a group of tribes, who lived on the Eastern Steppe, roughly described in the present Inner Mongolia reaching out in East and West. Here they had lived “allways”, or at least long before rise of written history.

The chinese characters for Xianbei means literally fresh new thieves.

The best known of the Xianbei peoples were the Xianbei-Tuoba tribe. They had their name after their sacred royal lineage, Tuoba. Following modern rules of pronunciation it must be pronounced something like “Tor-bar”, and I think, it means the descendants after “Tor”.

In China’s early history all the peoples on the plains were labeled as “-rong”, which means something like barbarians or natives. During the Qin dynasty (221 BC – 206 BC) and early Han Dynasty, most of peoples of the steppe were categorized as Xiongnu. Only after collapse of the the Xiongnu federation the Xianbei tribes appeared in the history under their separate names.

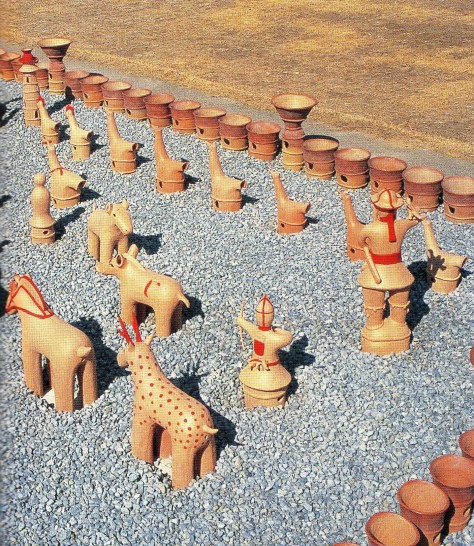

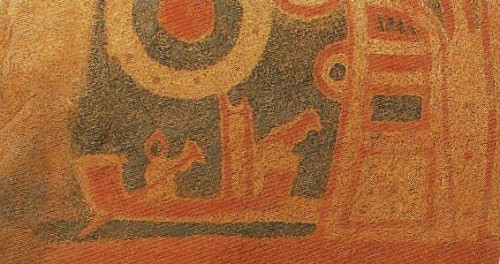

Typical Xianbei art – Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region Museum.

In the year 48 AC the before so mighty Xiong federation split up into two groups, the southern and the northern Xiongnu. An officer of the Han court named Zang Gong suggested that China should take advantage of the situation, ally with Xianbei and attack Xiongnu; but Emperor Guang Wu-di rejected firmly further acts of war. …

Typical Xianbei art – Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region Museum.

Supporters of Xianbei’s Mongolian origin bring forward to know that the Xianbei’s descendants, the Qi-Dans, mobilized their troops in military units called “Ordo”. Mongolian has a word with the same significance, “Ordu”, for example in “The Golden Horde” and other Genghis Khan’s armies. The word is found in Danish and English as “Horde,” but they think it comes from Mongolian. Therefore, since Xianbei’s descendants used a word, which the Mongols also used, they must have been of Mongolian ethnic origin, the supporters of the theory conclude

The Gaxian cave in the north-eastern Inner Mongolia.

Dokumentet “Wei Shu” is the story of Northern Wei, which was founded by the Tuoba Xianbei people. Here is told that in 443 AC a group of riders from a people called Wuluohou came and asked for an audience with the Emperor Tuoba Dai. They told him, they had heard about a cave, which was located in the northeastern part of the modern province of “Inner Mongolia”, today called “Oroqen Autonomous Banner.” The locals worshipped this cave as the Xianbei ancestral home, they said, convincing the king that the legendary cave, where all Xianbei’s common ancestors in ancient times had their original home, had been found.

“Wei Shu” says further that the king sent one of his men, Li Chang, out to investigate the matter. Li Chang found that the story was true and held various ceremonies on the spot to honor Xianbei’s indigenous ancestors. He did make an inscription on the rock at the cave, which described the ceremonies.

The cave and the inscriptions were explored by Professor M.I. Wenping in 1980. It has been inhabited since the Ice Age. It is today known as the Gaxian cave.

The Migration Time – The Five Hu Invade China

“Northern Wei” was founded by the Tuoba Xianbei people. It was the most important state in northern China in the years after the Migration Period, which in China was called the period of “Sixteen states” or the “Wu Hu” (five Hu) period.

It’s called “Five Hu” because China was invaded by the five “Hu” people, who were Xiongnu, Xianbei, Jie, Di and Qiang. …

The migration kingdoms in China in the period of the sixteen kingdoms – The migration from the steppe into China began, however, fifty to a hundred years before the similar event did in Europe.

In China, the ruling Jin Dynasty likewise were overrun by barbarian peoples from the steppe, who then turned against each other in an intense fight for the newly conquered land. The Xianbei people fought against various Xiongnu (Hun) peoples, The Murong and Tuoba Xianbei fought against each other. Most Chinese migration states lived in a more or less permanent state of war with their neighbors. When the dust settled, “Northern Wei” had through many years of fighting united almost all the barbarous nations in North China. To win the conquered people’s recognition they acquired Chinese culture and language, and they supported the spread of Buddhism.

Murong Xianbei’s Yan Kingdoms

All nations in North China in the Migration Period are often called something with “Former”, “Later”, “Northern”, “Eastern” and so on. These are all call names that modern historians have given them to keep track of the so many countries, whose name were the same.

Xianbei art could be a little strange – just as they later Qi Dan’s could also could be.

For example, there were six different kingdoms, who called themselves for “Yan”. There was the original Yan that existed in ancient China, while Socrates and Plato walked around in Athens. In addition there have been forms Yan (337-370), Later Yan (384-409), Northern Yan (409-436), Southern Yan (398-410) and Western Yan (384-394).

Most Yan kingdoms were created by the Murong Xianbei people. They were short-lived and extremely unstable. For example, “Western Yan” existed only for ten years, during which time they had seven different rulers, who all suffered an unnatural death.

About the Name Tuoba

Tuoba written in Chinese characters.

In Danish ears the word Tuoba sounds very much like Thor-far. “Thor” is the Scandinavian god of thunder, and “far” is the danish word for father. Therefore, I believe that Tuoba means “the descendants after Thor.”

The literal meaning of the two Chinese characters in simplified Chinese, which say Tuoba are “extension” and “postscript” and it does not really make any sense. It is clear that these two characters have been chosen because they best describe the pronunciation of the word regardless of their literal meaning….

So a qualified guess about the meaning of “Tuoba” will be that it means the descendants from an original ancestor, “Thor”.

The Chinese god of thunder has a hammer with a short handle, with which he produces the thunder.

Wei shu, the “Book of Wei”, was written by Wei Shou 551 – 554 AC. Here he tells that the name “Tuoba” comes from that the Tuoba Xianbei people descended from “The Yellow Emperor”, who is assumed to be the common ancestor of all Chinese.

Wei Shou lived during the Eastern Wei, who was that part of the split Northern Wei, who still held on to the hardboiled integration and kinesificerings policy, which was introduced in 494 AC. He used the Chinese royal name “Yuan”, which replaced the imperial family’s original name “Tuoba”, including for the emperors before 494 AC, and thus he creates some confusion.

He only tells about the Emperors of Eastern Wei and do not mention of the rivals in the Western Wei, who had rejected the integration policy and returned to the traditional Xianbei culture.

Not to applaud the racial policy of the state must undoubtedly have been politically incorrect, and probably harmful to health. So he could not very well write that the Xianbei people have one ancestor and the Chinese have another, it would probably have been quite dangerous. Moreover, after more than half a century’s intensively integration pressure, in an era where there were only a few books, maybe many could not remember the history of their people.

But he confirms that the name Tuoba contains a meaning of descending from an original ancestor….

The Creation of the Northern Wei Empire.

Tuoba Xianbei people came into the history in the kingdom of “Dai”. It was most likely located around the modern city of Hohhot in the modern Chinese province of “Inner Mongolia”.

In 341 AC king Tuoba Shiyijian of Dai lost his wife, who was a sister of king Murong Huang of “Former Yan”.

He asked Huang about a new wife. King Huang of Yan insisted, however, on a large sum of money for a new princess. King Shiyijian refused to pay and accompanied his rejection with abusive language. Then Huang sent his crown prince with an army against Dai, and King Shiyijian fled into the mountains with the whole of his people. The following year he sent his brother to Yan to ask for another wife, we don’t know if he succeded. Some months later came an envoy from the Murong kingdom to ask for a princess to the king. Kong Tuoba Shiyijian accepted the request from Yan and chose his own sister as a wife for Huang.

In 376 AC the kingdom of Dai was attacked by “Former Qin”, which was founded by the “Di” people, it is said. Tuoba people fled again into the mountains, and during their stay there king Shiyijian died. The invaders succeeded to conquer Dai, and it ceased to exist as an independent Tuoba kingdom….