The rooster was a universal solar symbol across Eurasia, the Near and Middle East and Europe as a bird that heralded the dawn with its crowing and that would dispel evil spirits as the light of day dispelled darkness. Veneration of the rooster in East Asia was particularly widespread, but is best known today and associated with Japan and China where the rooster is entrenched as the tenth of the twelve animal symbols in the Chinese zodiac.

The Chinese ideogram for rooster is 雞/鷄, 鸡 ( qi/chi/kai), homophonous to the one meaning “favourable” while the word for chicken crest is the same sound as that of an official (guān). Its appearance and its behaviour symbolize the “five virtues”: civil virtues, because its comb makes it look like a mandarin and therefore suggests advancement and promotion; martial virtues, because of its spurs; virtues associated with courage because of its conduct in battle; virtues in association with kindness, because it protects its hens; virtues related to confidence because of the accuracy with which it heralds the dawn. It also spoke of reliability, epitome of fidelity and punctuality. In Chinese Taoist and fengshui beliefs, the red cock or rooster on the walls of the house symbolizes protection of the house from fire; the white cock – protection from and chasing away demons. Five (cocks)- reminding parents to educate their sons (and hopefully daughters as well). Brilliant white in China is the color of purity and is linked with the Rooster. The Rooster’s direction is associated with West (death and burial).

In Japan, its crowing, associated with the raucousness of the deities, who lured Amaterasu, Goddess of the Sun, out of the cave where she had been hiding. Courage is the virtue that the Japanese (like other Far Eastern peoples) attribute to the rooster. The white cockerel as an auspicious symbol Japanese Shinto or shrine tradition likely has its origin in Taoist practices that filtered through from the Chinese court during the Tang dynasty and Nara periods. Chickens are thought of as errand messengers of the gods at the Isonokami Shrine where many sacred roosters are seen roaming.

In China, during the spring Hanshi festival the cock, like fire/sun, was considered a yang symbol and symbol of the sun, was temporarily extinguished and then relit. In Taoism, to have a rooster fight another rooster, stood for fire-renewal or regeneration … the rooster and the cockfight then takes its place as an indispensable spring ritual (although the Hanshi festival was eventually moved to coincide with the Qingming Festival or the Pure Brightness Festival which still includes the rooster and cockfight).

The dancing also recalls the raucous, erotic and ecstatic rituals of the Cock Festival (or Minam Bharani Festival) at Sri Kurumba Kavu in central Kerala is known for the raucous, erotic rituals. Thousands of devotees take part annually in the singing of highly explicit sexual songs and in the ceremonial pollution of the (attributed to Syrian/Hellenistic world influences) — see Scandalizing the goddess at Kodungalur

Comparing traditions, the Han Chinese myth of the divine archer Hou-Yi shooting three suns, the motifs of the sun palace and the celestial cock appear to have been mythical motifs that were separate, while some Miao versions have the merged myths of both Yi the archer shooting the sun as well as the sun entering the cave and refusing to emerge until the celestial cock crows. The story is set in the context of the reign of Emperor Yao, who is said to be ancestor to Han dynasty emperor Liu Bang or “the son of Emperor Ku and Qingdu, the emperor’s third concubine surnamed Chenfeng. Yao was also named “Yaotang Shi” and widely known as “Tangyao”, due to the land conferred upon him in Yao and Tang areas. At the age of 15, Yao began to assist his elder brother Emperor Zhi in ruling the country.”

The cave and rooster cult-myth of the Japanese is however closest to that of the Miao tribes of East and Southeast Asia, with whom the Japanese share the same M7 mitochondrial DNA ancestry or roots. The Miao/Hmong-Miao people are associated with cave culture. Their Dancing in cave Festival calls to mind the Japanese myth of the dancing that takes place to draw out the goddess Amaterasu from her cave. The Miao people have lived in the mountains since ancient times. The Dancing in Cave Festival of Miao people in Gaopo County lasts from the fourth day to the ninth day of the first lunar month every year. The jolliest event during the festival is dancing the Chinese Bagpipe Dance in caves. Miao people in Gaopo County said that celebrating the festival in caves is to honor their ancestors. Caves play a significant role in local Miao people’s daily life. Young people would choose caves to develop a romantic relationship; ancestors of Miao people even lived in caves; and caves were the place where the dead were buried…” — Dancing in Cave Festival From January 4 to 9 of every lunar year, the Miao people in Gaopo celebrates “Skipping Cave Festival” alongside the Lusheng dance in caves, which is intended to commemorate the lives of their ancestors as well as the traditions of the Miao ethnic group. In the Matang Village, 18 kilometers north of the city of Kaili, is a Gejia ethnic minority village, of the Gejia people who are classified as a subgroup of the Miao ethnic minority – the Gejia believe insist that they are the descendants of Houyi, the God of the Arrow, and the mythical marksman who shot down nine suns, leaving only the present one. His actions saved the world’s people from overheating and the drying up of all fresh water.

The chicken features in mortuary death rites and has the dual role “to guide the newly deceased family member’s soul to find the ancestral land” but also “In the process of Miao marriage, chicken is a symbol throughout every stage, from courting, proposal, betrothal, and wedding, to having children.” More is written about the symbolism of the rooster cock to the Miao below:

“Rooster divining: chicken in Miao myths To understand the symbolic meaning of the rooster divining ritual, we may turn to the cultural motif which recurs in Miao myths and legends. Using a rooster to predict the future of a marriage reflects its mystical function in the mind of the ancient Miao. There are various Miao sun-bird/ sun-rooster myths, which demonstrate that this ritual may have something to do with the association of bird/chicken with the sun. One of their widespread sun myths is about a rooster calling the sun out: long ago, there were twelve (nine in a different version) suns hanging in the sky. The people could not stand the heat aThe nd asked a brave hero to shoot eleven (or eight) of them by arrow, leaving only one. But the last sun was so scared that it hid, not daring to come out until a rooster started crowing (Pan, Yang, and Zhang 1997; Tapp 1989; Wu 2002). There is a similar myth popular in West Hunan (Lu 2000) and Southeast Guizhou (Bender 2006) about a hero who rides a golden pheasant to rescue the sun taken by a demon to bring life, joy, and hope back to the earth. These myths show that in Miao belief, the rooster is the medium connecting the secular and supernatural worlds; it is a sacred bird, a messenger of the sun god. It is capable of delivering requests for blessings to ancestors and gods in the supernatural world, and carrying messages about the future from the supernatural world to the Miao. This also explains the use of roosters in Miao funeral ritual for guiding the soul of the deceased to find the path leading to the realm of the ancestors … , in the Miao’s flood myths, the thunder god is in charge of the rain, and the image of the thunder god is a rooster.” – Chicken and Family Prosperity: Marital ritual among the Miao in Southwest China

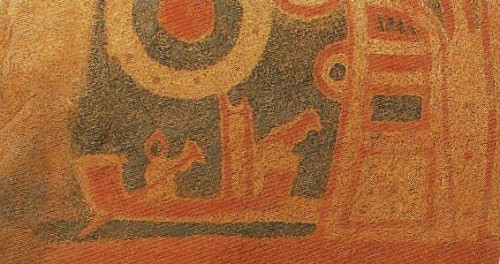

Above: Boat-of-the-dead rowing towards sun with rooster leading the way, Ikegami site of the Yayoi Period, Izumi city, Osaka; Below:

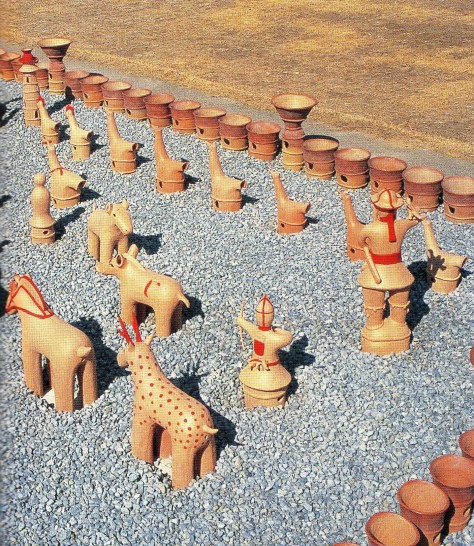

The cock as funerary and solar symbol in Japan dates back even earlier to the Yayoi period with the introduction of rice agriculture and then during Kofun Period where haniwa ceramic cocks and chickens were placed on top of tomb mounds. Haniwa chickens are found from the very beginning of the custom of placing these sculptures on tombs and they continue right through the period of haniwa use. Chicken form of haniwas appear in greater numbers than finds of other haniwa birds and are distributed from Kagoshima to Iwate Prefectures, a distribution, correlating to the distribution of kofun with haniwa…indicating a Yamato-nation-wide burial custom and Afterlife Worldview. Rarer than chicken haniwa, the cock is also seen in tomb mural paintings at the helm of a boat heading towards the sun.

Celestial sun-bird (rooster) and boat motifs seen in Kofun Period tomb mural

Cock symbolism in Kofun Period mortuary tomb haniwa

As seen from the reconstructed Kofun mortuary artefacts in the photo above, Japan probably derived its cock symbolism from the Mongolic/Xianbei/Hun-Xiongnu kurgan culture in Eurasia and East Asia, and Nara period symbolism from Tang China where it is an auspicious symbol, and not from its Tibetan lineages – since Tibetan Buddhism regards the rooster as an exceptionally ill-fated symbol (where it appears in the centre of the Wheel of Life, alongside the hog and the snake, as one of the three poisons, symbolizing lust, attachment and covetousness that put in motion the Wheel of the Law). The emerging from the sacred cave motif in the context Emperor Yao appears in the Korean royal founding myth of Tangun (Dangun)which suggests an affinity to the above-discussed emerging-from-the-cave traditions.

Gaxian Cave (Show Caves of China)

The location of this ancestral cave is thought to be Gaxian Cave is located in the Da Xing’an Range, 10 km northwest of Alihe (the administrative center of the Oroqen Autonomous Banner) in northern Inner Mongolia. This cave, whose southwest facing entrance is easily accessible from a small fluvial plain ten meters below, is 120 m deep and 22 m high. The surrounding landscape is covered by Manchurian primeval forest. In recent history, Gaxian Cave is known to have been used as an occasional shelter by Tungusic-speaking Oroqen hunters, the original inhabitants of the region.

A study of the cave was initiated in 1980 by Prof. MI Wenping, a prominent specialist on Manchurian archaeology and history, who upon his fourth visit to the cave, located on the west wall close to the entrance an engraved inscription comprising 19 lines of 201 Chinese characters. This inscription was in a style typical for the Northern Wei empire (386-581) and was a passage from the Wei Shu, the dynastic history, records the sending of a mission by the Wei emperor to visit an ancestral temple in his tribal homeland, It also contains a date equivalent to A.D. 443, was soon found to be almost identical to a passage in the Wei Shu, the dynastic history of the Northern Wei empire. Gaxian Cave may have been this ‘temple’. The ethnic group that established the Northern Wei empire is known historically as Tabgach (Tuoba) and thought to be the descendant of the Sienpi (Xianbei), both of which are believed to have been linguistically related to the later Mongols. Gaxian Cave thus provides tantalizing perspectives on early ethnic migrations in protohistoric Manchuria and Mongolia and the possibility that it may be common ancestral cave temple of the Wei Shu imperial mission, as well as of the Manchurian, Korean people of the Xianbei lineage. (Source: A visit to Gaxian Cave, Inner Mongolia Society for East Asian Archaeology (SEAA) – EAANnouncements 15 by Juha Janhunen)

In Korea, people “believed roosters knew time well and considered them a symbol of hopeful beginnings and good omens. It was said that when the chicken made sound, all evil spirits disappeared. The characteristic of intelligence was attributed to the rooster’s crest. When it eats, it shares its food with others, showing patience. A rooster stays awake all night and cries at a certain time every morning, giving an impression of trust. Its sharp toenail represents the science of war, and its continuing to fight until death was compared with bravery”. — Animals, Life in Korea

Sacred white rooster

Japanese white Yokohama cockerel (Photo: e-chickens.com)

In Japan, the white rooster is a sacred symbol, and it is allowed to run freely in Shinto temples where its morning call is thought to awaken the sun goddess Amaterasu. Roosters are seen at the Ise Shrine, where roosters are reminders of the rooster that crowed at dawn just as Amaterasu, the sun goddess was tricked into leaving her cave-grotto. According to e-chickens.com, the Japanese white chickens probably originated sometime in the late 16th Century in what was then Southern China and taken to Japan in the early 17th Century. The earliest long tailed fowl were found in China, but during the 17th century Japan became the centre for their development. The Japanese are said to be experts in keeping their tails growing all season. Japanese Bantam Chickens were first known as Chabo Chickens and are an old and well established ornamental Asian bantam breed.

Japanese Bantams, a.k.a. Chabo (Photo: John deSaavedra)

The white rooster is also a symbol of Lampang a province of Thailand. It is a symbol of the province adopted from one of the region’s oldest temple shrines; the Wat Phra Tat Lampang Luang Lampang, Thailand. Like in Japan where the rooster is depicted roosting on a tori arch, the white rooster is depicted seated in a ‘mondapa’ which is an arched structure with a pyramidal roof. The idea of the mondapa has in turn been derived from the ancient temple just named above. The Lampang Rooster Lampang has been further modified and incorporated within the design of Lampang province’s seal. A replica of the symbol of the white rooster can be seen adorning the horse carriages running on the streets of Lampang.

The Lampang Chicken icon

The white rooster is the “bird depicted on the Polish Coat of Arms. Often times, this chicken is incorrectly referred to as an Eagle or a Hawk. The Legend: This emblem originated when Poland’s original founder Lech saw a white chicken resting in it’s nest one early morning when he was out hunting. Lech hunted the bird while it rested in it’s nest, which was situated in a grassy valley in an area currently known as central Poland. He was so pleased with the ease at which this bird (chicken) was hunted, that he decided to settle there and placed rooster on his emblem (as opposed to the chicken that was originally hunted). … Lech decided to use a white rooster on his emblem instead of a chicken to symbolize the fact that the bird that rises earliest (the rooster) gets the easiest prey (the chicken resting in it’s nest). Initially, the emblem depicted a white Rooster. After generations and generations of being passed down, the rooster began being drawn as a white bird wearing a royal crown, paying respect to the Polish royal monarchs of the past. In later renditions, the original rooster was drawn as resembling a hawk or an eagle; This is what has led to the common modern misconception about the origin of the emblem.”

Rooster as fertility or sacred symbol in Southeast Asia

The rooster is also thought to counteract the evil influences of the dark night that it drives from the house if the inhabitants paint its effigy on their door.

The Miao (a.k.a. Hmong) people are traditionally animists, shamanists and ancestor worshipers with beliefs having been affected in varying degrees by Taoism, Buddhism and Christianity. At the Miao New Year there may be the sacrifice of domestic animals and there may be cockfights. The Hmong of Southeast Guizhou will cover the rooster with a piece of red cloth and then hold it up to worship and sacrifice to the Heaven and the Earth before the cockfight. The Miao are famous for their animal imitation dancing such as the cockfight dancing. In Shamanism in the Hmong culture, a shaman may use a rooster in religious ceremony as it is said that the rooster shields the shaman from “evil” spirits by making him invisible as the evil spirits only see the rooster’s spirit. In a 2010 trial of a Sheboygan Wisconsin Hmong that was charged with staging a cockfight, it was stated that the roosters were “kept for both food and religious purposes” resulted in an acquittal.”

In Vietnam, fighting roosters or fighting cocks are colloquially called “sacred chickens”.

The veneration of the traditional spirits (anito) is still practised in northern Philippines. Animist beliefs extend to the rooster and the cockfight, ”a popular form of fertility worship among almost all Southeast Asians”.

Kaharingan, an animist folk religion of the Iban branch of the Dayak people, accepted as a form of Hinduism by the Indonesian government, includes the belief of a supreme deity as well as the rooster and cockfight in relation to that of the spiritual and religious and some with the belief that humans become the fighting cocks of god, with the Iban further believing the rooster and cockfight was introduced to them by god. Gawai Dayak a festival of the Dayaks includes the cockfight and the waving of a rooster over offerings while asking for guidance and blessings with the rooster being sacrificed and the blood included in spiritual offering, while the Tiwah festival involves the sacrifice of many animals including the chicken as offerings to the Supreme God.

In East Timor, the roof of the house is reserved for gods and spirits of ancestors, the lower portion remains for the nature spirit and usually occupied by animals, and the cock is admired because of courage and perseverance, with the courage of a man compared with that of the cock, with the cockfight occurring regularly and “many tais designs include the cock”.

Aluk or Aluk To Dolo a sect of Agama Hindu Dharma as a part of religion in Indonesia, within the Toraja society and the people of Tana Toraja, embrace religious rituals such as the funeral ceremony where a sacred cockfight is an integral part of the religious ceremony and considered sacred within that spiritual realm. In several myths the cock has the power to revive the dead or to make a wish come true and is well known in Torajan cosmology.

Khasi people (with curiously Christian-like symbolism) believe the rooster is sacrificed as a substitute for man, it being thought that the cock when sacrificed “bears the sins of the man.

Out of India and Buddhist iconography

In India, hens and roosters were regarded as sun birds. They were named this way for their chickensong at sunset and by this allegedly warning people that evil spirits began wandering around the earth having just conquered the sun. Signing the end of the night at dawn, the roosters with their crowing were thought to let people know that the sun has gathered its power and conquered the evil spirits.

In India, it is the attribute of Skandha, personification of solar energy – also known as Lord Murugan. Skanda, is variously known as Lord Murugan a Bachelor god as well as the Kārttikeya/Kumara, the Warrior God of War, who wields a bow in battle. The lance called Vel in Tamil is also a weapon closely associated with him. The Vel was given to him by his mother, Parvati, and embodies her energy and power. His army’s standard depicts a rooster. [From Persia/Parthia/Kushan-Bactria to India? In the Iranian counterpart of Skanda, the Avestan deity Sraosa (which had its Sanskrit equivalent ‘Srausa’ which means “obedient messenger of the sun god”) is a killer of demons, like Skanda, has attributes of conqueror, protective martial deity for Zoroastrianism, and acts as the watchful and obedient messenger o f Ahura Mazda, and like Skanda, the cock is an animal sacred to the Sraosa. Sraosa is described in Pahlavi texts as repelling evil powers of the night with the help of a cock. According to Richard D Mann the earliest depiction of Skanda/Karttikeya with a cock and cock statuary comes from Mathura and dates to the Kushana era. The author suggests Parthian coinage influence upon the Bactrian-Kushans and that bird-falcon association with Parthian warrior gods was borrowed by Kushan/Bactrians, and that a Bactrian legend in Greek script identifies the figure holding bird-topped standard found on Kushan coins to be the Hindu-Kushan deity Mahasena. Mann (at p. 126) notes that “all of the cock statues with the bird/cock from the Kushana era occurs in an area geographically close to Parthia, where Scythian and Parthian culture spread … owes its presence on these statues to those cultures….The cock itself relates these images of Mahasena to another Iranian martial deity Sraosa”. According to Mann, Sraosa was assimilated with Indian Karttikeya, the Avesta Mithra is flanked by Rasnu and Sraosa, the latter pair is thought to be the origin of the Indian Purana’s Rajna and Srausa. In Pahlavi texts:

“The cock is created to oppose demons and sorcerers, as a collaborator of the dog. As He says in the Religion: those are the material creatures, those are the collaborators of Sros [Sraosa], the dog and the cock … for that cock, they call the bird of righteous Sros. And when it crows, it keeps misfortune away from the creation of Ohrmazd”

Hence, we have two schools of thought, one, that cock symbolism in India originated from the Iranian/Parthian/Bactrian quarter, while the other sees cock symbolism as indigenous to India and hailing from much older fertility cults or festivals. [We break in here to suggest that the beloved folk Jizo deity is likely the Japanese counterpart to Sraosa/Srausa as Jizo is also seen as Conqueror/Victor of death, navigating the Underworld assisting hapless humans, especially children, and equally associated with the appearance of cocks, and their crowing at dawn dispersing the demons in Japanese folklore, although the Jizo icon was later transformed into a bodhisattva with the arrival of Buddhism and the cock association sometimes lost.]

Kukkuta Sastra (Cock Astrology) is a form of divination based on the rooster fight and commonly believed in coastal districts of Andhra Pradesh, India. It is prevalent in the state, especially in the districts of Krishna, Guntur, East Godavari and West Godavari and the Sankranti festival.

Cocks and cockfighting have been depicted on Indus valley seals and Tamil cities have been named cock-cities which is believed to have occurred with the migrations of the Dwarakans (at about 1,500 B.C. at the end of the Indus civilization) who brought the word “kozhi” for cock and cockfighting practices to pre-existing Tamil lands such as Kerala, Calicut, Urayur, all cock cities associated with kozhi. Cock fighting is a traditional pastime, known also as the 43rd Womenfolk were particularly good at the art and gaNikas (courtesans) of Royal court since the times of Ramayana were trained in the 64 arts including the cock fights.

Despite being forbidden in the Vedic philosophy of sattvic Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism. Theyyam deities are propitiated through the rooster sacrifice where the religious cockfight is a religious exercise of offering blood to the Theyyam gods. A popular Hindu ritual form of worship of North Malabar in Kerala, India is the Tabuh Rah blood offering to the Theyyam gods. Scandalizing the goddess at Kodungalur is a study of the Cock Festival (or Minam Bharani Festival) at Sri Kurumba Kavu in central Kerala is known for the raucous, erotic, and insulting devotional practices of its participants. Thousands of devotees take part annually in the singing of highly explicit sexual songs and in the ceremonial pollution of the goddess Sri Kurumba’s shrine. This festival is controversial but popular, and resembles in many ways descriptions of the ecstatic cults of the ancient Near East that spread throughout the Greco-Roman empire. Oracles of the goddess, called veliccappatus (illuminators), reveal her wishes through trance and in their possessed state cut their foreheads with swords as they dance.

In 2011 the Madras High Court Bench ordered the rooster fight at Santhapadi and Modakoor Melbegam villages permitted during the Pongal religious festival. Again in 2011 a public interest litigation petition caused the Madras High Court Bench to grant permission to villagers of Kodaioor village to conduct a rooster fight during Deepavali coinciding with a local temple festival from the claims that the “villagers’ religious sentiments would be hurt if the cockfight was not allowed “. In many parts of India, tribal or folk deities are propitiated through cock sacrifice.

Bayon Temple is an ancient Buddhist temple that also incorporates elements of Hindu cosmology (see next section) includes “a depiction of a cockfight” within the walls of the temple which continues today within a debate of “religious sanctity”.

With the rambling strutting roosters of the Buddhist temple of Wat Suwankhiri on a Payathonsu cliff near by, during April, Three Pagodas Pass becomes a site of the Songkran Festival with cockfights.

Sacred Buddhist amulets are made within that religious schema, created and blessed in various temples in Thailand, many depicting Buddha with cocks in fighting stance, sacred within that religion.

Balinese Hinduism also includes the religious belief of Tabuh Rah, a religious cockfight where a rooster is used in religious custom by allowing him to fight against another rooster in the religious and spiritual cockfight of the Balinese Hinduism spiritual appeasement exercise of Tabuh Rah. The altar and deity Ida Ratu Saung may be seen with a fighting cock in his hand with the spilling of blood being necessary as purification to appease the evil spirits. Ritual fights usually take place outside the temple proper and follow an ancient and complex ritual as set out in the sacred lontar manuscripts.

Cocks in Hinduism

Makar Sankranti is a Hindu festival dependent on the position of the sun and celebration of Sankranti who is considered a Deity for Hindus and is celebrated in many ways including worship for the departed ancestors and to worship Saraswati. In the western Indian state of Gujarat, an event of the Makar Sankranti festival is kozhi kettu, the rooster fight. Kozhi kettu is an ancient ritual of Tulunadu and an ancient ritual associated with the ‘daivasthanams’ (temples) there. Kozhi kettu organized as part of religious events are permitted.

Feathers have been ruffled and controversy brewed when some Hindu temples used a symbol of a peacock rather than a rooster on their flags for Kavady festivals. Gonaseelan Moopanar, chairman of the Hindu temples foundation, confirmed that the rooster was the correct symbol, not the peacock saying, “According to religious scriptures and the teaching of our elders, the rooster is the correct symbol. It has been the symbol for many years. “The peacock symbolises the transport for Lord Muruga, but the rooster is the victory flag.”

Cockfighting arrived in Bali, Indonesia, it is not known when, but probably together with Hindusim. Cockfights,called tajen, meklecan or ngadu, in Balinese, are part and parcel of temple and purification (mecaru) ceremonies. The Tabuh Rah ritual to expel evil spirits always requires a cockfight to spill blood. Tabah Rah literally means pouring blood. There are ancient texts disclosing that the ritual has existed for centuries. It is mentioned in the Batur Bang Inscriptions I from the year 933 and the Batuan Inscription from the year 944 (on the Balinese calendar). The blood of the loser spills on the ground, an offering to the evil spirits.

The origin of cockfights: Cock fighting is said to be the world’s oldest spectator sport and was entrenched in ancient India, China, Persia, and other Eastern countries, and was introduced into Ancient Greece in the time of Themistocles (c. 524–460 BC). In Persia, the sport goes back 6,000 years in Persia and the term “Persian bird” for the cock or fighting cock,is thought to have been given by the Greeks after Persian contact “because of his great importance and his religious use among the Persians”. It is however noted that even long before that time, in Iran, during the Kianian Period, from about 2000 B.C. to about 700 B.C., “the cock was the most sacred” bird. It is also thought that cockfighting has its origin in the Indus Valley Civilization, and spread from South Asia after the Persian armies conquered India in the 4th century B.C. The Persians adopted the sport and are thought to be at least partly responsible for its introduction to the Mediterranean basin through military and commercial pursuits. The sea-faring Phoenicians are also thought to be responsible for the widespread distribution of gamefowl from the orient to Africa, the Middle East, and along the European coast (source: Encyclopædia Britannica (2008) and History of Aseel (old game breed)).

***

In the Near East in the ancient land of Babylonia (including modern day Iraq), there is the lore of the True Shepherd of Anu(SIPA.ZI.AN.NA – Orion and his accompanying animal symbol, the Rooster, with both representing the herald of the gods, being their divinely ordained role to communicate messages of the gods. “The Heavenly Shepherd” or “True Shepherd of Anu” – Anu being the chief god of the heavenly realms. On the star map the figure of the Rooster was shown below and behind the figure of the True Shepherd, both representing the herald of the gods, in his bird and human forms respectively.[Source: “Rooster“, Wikipedia]

Nergal, an idol of the Assyrians, Babylonians, Phoenicians, and Persians, whose name means, “a dunghill cock.”(Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, Brewer, 1900) Astrological mythology of the Assyrians and Babylonians was that the idol “Nergal represents the planet Mars, which was ever the emblem of bloodshed”

The Middle East and the rooster in Judaic tradition

Arab and Islamic traditions: In pre-Islamic Arabia, Arab Bedouins attributed generosity to the cock. In Islam, the rooster enjoys a particular veneration. The Prophet himself is alleged to assert that the white rooster is his friend because it announces the presence of the Angel. Moreover, the Prophet is said to prohibit cursing the rooster, which calls to prayer. In Islamic dream analysis, both snake and rooster are interpreted as symbols of time.”

The cock is a divine Islamic symbol – in the words of Muhammad of that Abrahamic religion in one of the six canonical hadith collections of Sunni Islam, stating that of “when you hear the crowing of cocks, ask for Allah’s Blessings for they have seen an angel” as well as the mention where “the cock is also venerated in Islam: it was the giant bird seen by Muhammad in the First Heaven crowing.”

Judaic tradition: Although rooster worship is considered by some within the Judeo-Christian ethic as a form of Baal or Baalim worship, rooster (Gallus domesticus) bones were identified at Lachish dating to early Iron II”, in Palestine, the earliest chicken bones are present in Iron Age I strata in Lachish and Tell Hasben”.

And in excavations at Gibeon, near Jerusalem, dating to the seventh century B.C., potsherds were found incised with cocks and “some of them placed within the six-pointed star of the Magen David.” The seal of Jaazaniah carries the insignia of a rooster from the ruins of the biblical Judean kingdom at Mizpah, with the inscription of “belonging to Jaazaniah, servant to the king”, the first known representation of the chicken in Palestine, and from II Kings 25:23, we know of one Jaazaniah the Maschathit, who was an official under Gedalish at Mizpah.

The Zohar (iii. 22b, 23a, 49b), the book of Jewish mysticism and collection of writings on the Torah written by first century tannaic sage Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai (Rashbi), tells of a celestial manifestation, which causes the crowing of the roosters; known also in the Talmud, is “blessed be He who has given the cock intelligence,”(Ber. 60b) and as well as Job 38:36 in the Douay-Rheims Bible.

“In the rabbinic literature, the cockcrow is used as general marking of time”, and some of the Sages interpreted the “cockcrow” to mean the voice of the Temple officer who summoned all priests.

Levites, and Israelites in the context of their duties and used, the Hebrew gever was used to mean a “rooster” in addition to the meaning of “man, strong man”. Saʻadiah ben Yosef Gaon(Saadia Gaon) identifies the definitive trait of “a cock girded about the loins” within Proverbs 30:31(Douay–Rheims Bible) as “the honesty of their behavior and their success”, identifying a spiritual purpose of a religious vessel within that religious and spiritual instilling schema of purpose and use, within Judeo-Christian traditions. The Hebrew term zarzir, which literally means “girt”; “that which is girt in the loins” (BDB 267 s.v.) is recognized in the Targum as well as the Chaldaic, Syriac, Arabic, LXX and Vulgate with all referencing the fighting rooster of fighting cock as the religious vessel. The ancient Hebrew versions identified the Hebrew “a girt one of the loins” of Proverbs 30:31 as a rooster, “which most of the old translations and Rabbis understood to be a fighting cock”, with also the Arabic sarsar or sirsir being an onomatopoeticon or onomatopoeia for rooster(alektor) as the Hebrew zarzir of Proverbs 30:31.

In the Jewish religious practice of Kapparos, a rooster as a religious vessel is swung around the head and then sacrificed on the afternoon before Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. The purpose of the sacrifice is the expiation of sins of the man as the animal symbolically receives all the man’s sins, which is based on the reconciliation of Isaiah 1:18. The religious practice is mentioned for the first time by Natronai ben Hilai, Gaon of the Academy of Sura in Babylonia, in 853 C.E., who describes it as a custom of the Babylonian Jews and further explained by Jewish scholars in the ninth century by that since the Hebrew word geber(Gever)[62] means both “man” and “rooster” the rooster may act or serve as a palpable substitute as a religious vessel in place of the man with the practice also having been as a custom of the Persian Jews.

In Iran during the Kianian Period, from about 2000 B.C. to about 700 B.C., among domestic birds, “the cock was the most sacred” and within that religion, the devout, “had a cock to guard him and ward off evil spirits Zoroastrianism, claimed to be “the oldest of the revealed world-religions” and founded by the Prophet Zoroaster (or Zarathustra) opposed animal sacrifices but held the rooster as a “symbol of light” and associated the cock with “good against evil” because of his heraldic actions.

From Anatolia to the Greco-Roman world and Europe

Plutarch said the inhabitants of Caria carried the emblem of the rooster on the end of their lances and relates that origin to Artaxerxes, who awarded a Carian who was said to have killed Cyrus the Younger at the battle of Cunaxa in 401 B.C “the privilege of carrying ever after a golden cock upon his spear before the first ranks of the army in all expeditions” and the Carians also wore crested helmets at the time of Herodotus, for which reason “the Persians gave the Carians the name of cocks”. It is Carites in 2 Kings 11 who were used by Jehoiada to protect Joash son of Ahaziah of the line of David, ancestor to Christ from Athaliah.

Good Shepherd fresco from the Catacombs of San Callisto with the cock at His right hand

The Rooster Symbol in Europe

The Rooster symbol in Europe is borrowed from many directions – Anatolia, Greco-Roman traditions and Judaic-Christian traditions.

The sacrifice of a cock and a ritual cockfight was part of the Imbolc festivities in honour of the pan-Celtic goddess Brighid.

“In Greek tradition Velchanos the Cretan rooster-god was assimilated to Zeus. A rooster was standing beside Leto, pregnant by Zeus, when she gave birth to Apollo and Artemis. Thus the rooster is dedicated to solar gods as well as to lunar goddesses. Moreover, the rooster is the specific attribute of Apollo. A rooster was ritually sacrificed to Asclepios, son of Apollo and god of medicine, because the bird heralded the soul of the dead that it was to guide to the Otherworld. Asclepios is also the god who, by his healing powers, brought the dead back to life on earth. This is precisely the reason why the rooster was also the emblem of Attis, the oriental Sun-God, who died and came to life again. This also explains why the rooster is attributed to Hermes, the messenger who travels the three levels of the cosmos. The rooster, along with the hound and the horse, is among the animals offered in sacrifice in the funeral rites of the ancient Germans. In Norse traditions, the rooster is symbol of soldierly vigilance, posted on the topmost branches of the ash Yggdrasil to warn the gods when the giants, their foes, are preparing to attack. When the bird is set on church spires, it assumes the role of protector and guardian of life. ” — “The Rooster” the New Acropolis International Philosophical Organization (see Readings below)

The Talmud makes the rooster a master of courtesy because it heralds his Lord the Sun with its crowing. In the Book of Job, the rooster is the symbol of God-given intelligence while the ibis is the symbol of wisdom and the Judaic tradition carried over cock-as-victor-over-resurrection symbolism to Christianity. The cock was considered an emblem of Christ, like the eagle and the lamb, symbol of Light and resurrection. The rooster or cock as a religious vessel found in the Catacombs from the earliest period including a painting from the Catacomb of St. Priscilla (mentioned in all the ancient liturgical sources and known as the “Queen of the Catacombs” in antiquity) reproduced in Giovanni Gaetano Bottari’s folio of 1754, where the Good Shepherd is depicted as feeding the lambs, with a crowing cock on His right and left hand. Likewise as well within the Christian “Tomb of the Cocks” in Beit Jibrin, which was a Palestinian Arab village located 13 miles northwest of the city of Hebron and part of the Kingdom of Israel, “we find two spirited cocks painted in red in the spandrels with a cross just over the center of the arch”. Similarly a multitude of sarcophagi are found with the rooster and the sacred cockfight with the understanding of striving for resurrection and eternal life in Christianity. This sacred subject carved on early Christian tombs, where the sepulchral carvings have an important purpose, “a faithful wish for immortality, with the victory of the cock and his supporting genius analogous to the hope of resurrection, the victory of the soul over death”. Similar illustrations of cocks in fighting stance are found within the Vivian Bible as well as the fighting cocks capitals in the Basilica of St. Andoche in Saulieu and the Cathédrale Saint-Lazare d’Autun provides “alternate documentation” of the rooster and the religious, spiritual and sacred cockfight.

All four canonical gospels state that, during the Last Supper, Jesus foretold of Peter’s denial (Saint Peter) and that he would deny Christ three times before the cock’s crow. Augustine of Hippo, Catholic saint and pre-eminent Doctor of the church understood “a visible sign of an invisible reality” of the rooster to include that as described by St. Augustine in DeOrdine as that which “in every motion of these animals unendowed with reason there was nothing ungraceful since, of course, another higher reason was guiding everything they did”.

Vatican Persian Cock – A 1919 print of a fabric square of a Persian cock or a Persian bird design belonging to the Vatican (Holy See) in Rome dating to 600 C.E. The halo denotes its divine status.

The cock for the Vatican is a Persian cock denoting a sacred and religious vessel. In the sixth century, it is reputed that Pope Gregory I declared the cock the emblem of Christianity saying the rooster was “the most suitable emblem of Christianity”, being “the emblem of St Peter”. Some say that it was as a result of this that the cock began to be used as a weather vane on church steeples, and some a Papal enactment of the ninth century ordered the figure of the cock to be placed on every church steeple. It is known that Pope Leo IV had the figure of the cock placed on the Old St. Peter’s Basilica or old Constantinian basilica and has served as a religious icon and reminder of Peter’s denial of Christ since that time, with some churches still having the rooster on the steeple today. A Dictionary of the Bible” which tells us that “Pindar (ca. 522–443 BC), mentions the cock, Homer (ca. 800–750 BC) names a man “gever” the word for a cock and Aristophanes (ca. 446 BC – ca. 386 BC) calls it a Persian bird.” In Portugal, the rooster is a symbol of justice and faith in God.

However, given the antiquity of solar symbolism in Europe, alternative reasons for cock symbolism may have been derived from the Celts, or the Goths or along with the proliferation of the Roman cult of Mithras where the rooster was the symbol of the sun god and the Orphic bird of resurrection. The cockerel was already of symbolic importance in Gaul at the time of the invasion of Julius Caesar and was associated with the god Lugus. The most important evidence of the cultic practices of Mithraic Mysteries was the find in Moesia and Thrace, in Bulgaria, of the square stone of Novae/Steklen depicting on the lateral faces Cautes carrying a cock held upside-down and Cautopates a cock or other bird held upright (both in addition to their torches). The find dates the arrival of a cult in the Danube to the 1st century. or the very beginning of the 2nd. Cautes carries the inverted bird. The torch-bearers wear pillei not in the Phrygian style, a long ray links the raven to Mithras’s head. The ray extending to Mithras is very carefully modelled to give the impression of penetration through the vault surrounding the bull tauroctony – it emerges from a hollow specially cut on the inside the vault. A small lion’s head is carved on the rocky cave below Sol the sun god. The serpent coiled around the feet of Cautes. [recall solar symbolism, sun-god, cock and cave cult of East Asia – which influenced which?]

During the Punic wars, the specialist bird watcher, the Roman augur, who was advisor to ruler and king, would observe the chickens to tell whether or not a proposed course of action had the approval of the gods. The Roman augur did not stay in Rome when there were wars being waged. Sacred chickens were taken on the road and to the field with them in times of war.

In 256 BC, a Roman army led by the consul Regulus invaded Africa, but at Carthage, the Romans encountered a far superior army to those they had defeated in Sicily. A large army, led by the Spartan Xanthipus, defeated the Romans and captured Regulus. The Roman army retreated, and while sailing back towards Sicily a large storm came and destroyed the rest of the fleet. During Carthaginian War II the armies of Carthaginians predominantly gained victories, especially under the leadership of the famous commander Hannibal. Undeterred, the Romans sent a new invasion fleet in 254 B.C., which was also sunk by a storm. But despite their victories, the Carthaginians were weary of war, sent Regulus, who had now been a prisoner for five years, back to Rome to negotiate the terms of peace. Regulus on his part swore that he would return to Carthage upon the completion of his mission. When he arrived in Rome, he went before the Senate and told them to continue the war and not make peace.

Claudius Pulcher, now in charge of the Roman fleet, caught sight of a Carthaginian squadron. As was the custom for the Romans, he performed the necessary auguries before the sea-battle of Drepanum between Rome and Carthage in 249 B.C… grain was offered to chickens, and see if they would eat. When this was performed, the chickens refused to eat. Angry, Claudius Pulcher took the chickens and tossed them overboard, saying “If they will not eat, then let them drink!” The superstitious military chiefs, soldiers and sailors believed the augurs, and are thought to have lost heart, and failed to put up resistance to the Carthaginians. Consequently, Claudius’ fleet was defeated by the Carthaginians. When Claudius returned to Rome, he was put on trial and fined heavily, not for losing the battle but for ignoring the will of the gods.

Another notable occasion was the morning of the battle of Lake Trasimene in 217 BC, during the Second Punic War, when the consul C. Flaminius ignored the auguries with disastrous results.

French coin

French coin

Today the Gallic rooster is an emblem of France and adorned the French flag during the French Revolution. In the Bayeux Tapestry of the 1070s, originally of the Bayeux Cathedral and now exhibited at Musée de la Tapisserie de Bayeux in Bayeux, Normandy, there is a depiction of a man installing a rooster on Westminster Abbey. From 16th century onwards representations of a cockerel accompanied the King of France and French royal coinage. The cock appears on the coins struck under both the Valois and Bourbon kings. Napoleon III however, was said to have disliked the cockerel, which nevertheless, virtually became an official symbol of the Third Republic: the gates of the Elysée Palace, erected at the end of the 19th century, feature a cockerel.

The gallic rooster is also an emblem of French-speaking Wallonia in Belgium and Denizli.

Flag of Wallonia (French-speaking region of Belgium)

The ancient Greeks amused themselves with cock games. The cock was a sacred symbol of Apollo, and also associated with his son, Asklepios, the healergod, associated with the life-giving force of the sun. Phemistocles, a famous Athenian statesman, strategist and commander, according to legend, proposed to include the review of cock games in the program of military training during the Greco-Persian wars … he allegedly said, “Let the young warriors see how selflessly the roosters fight, and learn firmness and bravery from them”. Frazer (2006: p. 106) in The Golden Bough wrote: “In modern Greece, when the foundation of a new building is being laid, it is the custom to kill a cock, a ram, or a lamb, and to let its blood flow on the foundation-stone.”

A belief arose in medieval times that the black cockerel was a symbol of witchcraft along with the black cat, and the rooster continued to be “used as symbols of either virtue or vice” till modern times. A white cockerel is thought universally to be lucky whilst the dark cockerel attracts negative energies, and in some parts of Europe was thought to be in league with the Devil and foretold death in the family. In 19th-century-Styria, a province in Austria, jaundice(hepatitis) was treated by placing yellow hens close to the ill person and the disease driven into the chickens through conjuring and wailing.

Rooster symbolism in more recent times

In the 20th century, Imbolc was resurrected as a religious festival in Neopaganism, specifically in Wicca, Neo-druidry and Celtic Reconstructionism.

During World War I, an organization entitled, Order of the White Feather got men men to enlist in the British Army by telling women to present men do did not enlist in the army with a white feather, that symbolized cowardice? Men with wives and children decided to join the army because their masculinity were questioned when they had not enlisted. Women would stick a white feather on the coats and jackets of men who did not enlist to ridicule them. According to Wikipedia, “The white feather as a symbol of cowardice comes from cockfighting and the belief that a cockerel sporting a white feather in its tail is likely to be a poor fighter. Pure-breed gamecocks do not show white feathers, so its presence indicates that the cockerel is an inferior cross-breed.”

In Japan, since the Edo Period, the Tori no ichi, a market fair has been held on the Days of the Rooster in November (to welcome the New Year) at various Otori-jinja shrines found in all parts of Japan. This fair is sometimes called by the familiar name of Otori-sama. The patron deity of good fortune and successful business is enshrined at Otori-jinja shrines. Open-air stalls are set up selling among other things, kumade rakes (symbolic of the rooster’s feet) for ‘raking in wealth and good fortune.’This good-luck rake is made of bamboo and is decorated with masks and koban (old gold coins).

Tori no Ichi is held at Temple of Tori (Juzaisan Chokoku-ji) in Asakusa, Tokyo, but it moved there, originally from moved Hanamatamura. The origin of Tori no Ichi Fair was a fair of Hanamatamura , a harvest festival celebration by peasants who thank to Hanamata Washidaimyojin. On the day of the festival, Ujiko(people under protection of the local deity) dedicated a rooster to Hanamata Washidaimyojin and after the festival they went to the most famous temple “Senso-ji” in Asakusa and released the collected roosters in front of the temple. Similar fairs are also held at various shrines of the Washi (Eagle) – numbering about 30 other shrines in Tokyo such as Hanazono-jinja Shrine in Shinjuku-ku, Kitano-jinja Shrine in Nakano-ku and Ebara-jinja Shrine in Shinagawa-ku.

The Rooster fair at Otori-jinja Shrine is believed to have begun during the Oei era at the beginning of the 15th century (the period spanned the years from July 1394 through April 1428). The new era name was created because of the plague that struck in the preceding one, which leads us to surmise that one of the reasons the Rooster symbol was adopted was to dispel the evil spirits or demons of disease. A poet, KIKAKU who was a pupil of the most famous Japanese poet Mastuo Basho, said for Tori no Ichi “Haruwomatsu Kotonohajimeya Tori no Ichi” (Tori no Ichi is a first important event to bring New Year.). The rooster appears to have fire (solar) associations – the day of the Tori (Rooster) comes every 12 days in November and it is said that a fire is likely to take place in the year that the day of the Tori has 3 times.

Chicken DNA and the domestication of the chicken

Chicken myths across cultures and civilizations in many countries show common components, and likely originated with the peoples who domesticated the chicken, traveling with them as they migrated or traded. Chickens are established by DNA research to have come from the Gallus gallus bankiva wildfowl which live in the jungles of South and South-East Asia, but that Gallus sonneratii has also contributed to the genetic make-up of the domestic chicken. Mitochondrial DNA research data suggests that one continental population of red junglefowl Gallus gallus gallus, probably from Thailand, is likely at the maternal origin of all domestic chicken stock. Chickens are however, thought to have been domesticated independently in various places in Asia, including India‘s Indus Valley (where the chicken population expanded the most) as early as 3,200 BC,and brought from India to Persia by the soldiers of Tsar Darius I, returning from a campaign. From Persia, chickens spread to Egypt, then to Greece, and by trade routes to Sicily and Rome, Italy and from there to the rest of Europe. Historians have noted that the bird is not represented on Egyptian monuments, and that it appeared in Babylonian art only in the late Persian period. Out of Southeast Asia, the chicken spread to Japan, Java and the Philippines, etc.

Sources and References:

“The Rooster” the New Acropolis International Philosophical Organization

Dancing in Cave (Cultural China website)

Chicken and Family Prosperity: Marital ritual among the Miao in Southwest China by Xianghong Feng

A visit to Gaxian Cave, Inner Mongolia Society for East Asian Archaeology (SEAA) – EAANnouncements 15 by Juha Janhunen

The Myth of Gojoseon’s Founding – King Dan-gun

Scandalizing the goddess at Kodungalur

The Sacred Birds (on Roman augury)

Animal Symbolism Animals’ Symbolism In Decoration, Decorative Arts, Chinese Beliefs, and Feng Shui.

The Gallic Rooster (History of Provence and France)

The Rooster: A Symbol of Portugal

Origin and domestication of chicken: a mitochondrial DNA perspective by O. Hanotte, paper presented at the Chicken diversity consortium

Genetic evidence from Indian red jungle fowl corroborates multiple domestication of modern day chicken by Sriramana Kanginakudru et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2008, 8:174

Chicken domestication: from archeology to genomics. C R Biol. 2011 Mar;334(3):197-204. by Tixier-Boichard M

Marked by the sign of the rooster (Zoom Central Asia)

Midsummer: Magical Celebrations of the Summer Solstice by Anne Franklin (p. 177)

Dacian monuments: Mithraic studies in BulgariaForts., Volume 2; Volume 14; Volume 17 by Wolfgang Haase, Hildegard Temporini

Haniwa Birds, by KAKU Takayo Nihon Kokogaku 14, November 2002 ISBN 4-642-09089-4 ISSN 1340-8488, ISBN 4-642-09089-4

Our Yokohamas (e-chickens.com)

Iranian Sraosa and the Indian Skanda by Sukumar Sen

The Rise of Mah Sena: The Transformation of Skanda-K Rttikeya in North India from the Ku A to Gupta Empires by Richard D. Mann

Ancient tales in modern Japan: an anthology of Japanese folk tales by Fanny Hagin Mayer

How the chicken conquered the world by Jerry Adler and Andrew Lawler Smithsonian magazine, June 2012

The Cocks in Indus seal and the Cock-city in Tamilnadu. World Tamil Conference series 16

Sacred cockfight (Wikipedia)

The origin of the Tori no ichi Fair (Rooster Market Fair Day)

[…] “…the Han Chinese myth of the divine archer Hou-Yi shooting three suns, the motifs of the sun palace and the celestial cock appear to have been mythical motifs that were separate, while some Miao versions have the merged myths of both Yi the archer shooting the sun as well as the sun entering the cave and refusing to emerge until the celestial cock crows.” Read more. […]

[…] The roads here are full of trucks, cars, motorcycles, bicycles, bull carts and many many pedestrians. Here is a truck of sand (and we saw hundreds of these kinds of trucks) delivering sand to build roads, commercial buildings and homes as the area is growing so quickly due to the tech industry. The decorations on the truck belong to a certain truck-owning family. The peacock is the bird of India and the rooster is the symbol of the deity they pray too. In India, the rooster or cock is the attribute of Skandha, personification of solar energy – also known as Lord Murugan. Skanda, is variously known as Lord Murugan a Bachelor god as well as the Kārttikeya/Kumara, the Warrior God of War, who wields a bow in battle. The lance called Vel in Tamil is also a weapon closely associated with him. The Vel was given to him by his mother, Parvati, and embodies her energy and power. His army’s standard depicts a rooster. (https://japanesemythology.wordpress.com/rooster-symbolism/) […]

[…] über Rooster symbolism […]